On 26 April, either Emmanuel Macron or Marine Le Pen will be elected the next president. Even though Macron and Le Pen already confronted each other in the second round of the 2017 elections, this time the radical left has come third, with only 1.2 percentage points behind the far right.

On 26 April, either Emmanuel Macron or Marine Le Pen will be elected the next president. Even though Macron and Le Pen already confronted each other in the second round of the 2017 elections, this time the radical left has come third, with only 1.2 percentage points behind the far right.

In this elections, the recomposition of the political field towards a tripartition continues: extreme right, the liberal centre, and the radical left. The Socialist Party and the Republicans have almost disappeared.

The way in which these three blocs have consolidated during this first round, agglomerating 73% of the votes: Macron (liberal La République en Marche !) 27.84%, Le Pen (far right Rassemblement National, RN) 23.15%, and Jean-Luc Mélenchon (radical left La France insoumise) 21.95%. This allows us to ascertain the new power relationships. Among the 9 other candidates, only Zemmour (7%) is above the 5% mark (below 5% it is not possible to get campaign expenditures reimbursed).

Macron: The bourgeois bloc

The disappearance of the Republican party

In 2017, Macron had been elected largely by former reformist left voters, virtually leading to the disappearance of the Socialist Party (PS). This year, Macron has specifically tried to convince left voters again through his management of the health crisis and a ‘whatever it takes’ approach. But first results show that this time, it was the right that voted for him, leaving the Republican party (Les Républicains) itself way behind. Thus, among the voters of Valérie Pécresse’s predecessor, François Fillon, in 2017, 38% have voted for Macron this time, and only 20% for the Republican candidate who garnered only 4.8% in total.

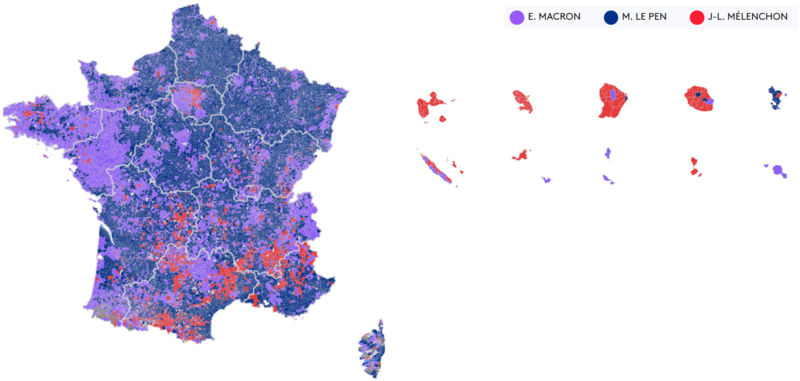

This dynamic is confirmed from a territorial point of view, since Macron is taking the historical bastions of the Republicans such as the 16th district of Paris and the bourgeois towns of the Hauts de Seine and Yvelines departments. Socially too, since he achieves his best results among the wealthy electorate (43%), the over 65 year olds (39%), the executives and intermediate professions (34%), but receives only a relatively small share of votes among the working classes (18%).

If the social structure of Pécresse’s voters remains the same as that of the traditional electorate of the Republican right (urban, older, executives, and business owners), very few of them voted for her. This is due to a campaign that failed to take off, and Macron, who was more convincing than her with largely similar proposals (retirement at 65 years of age, Income of Active Solidarity, RSA – earned income supplement, a form of welfare – conditioned on fifteen hours of activity per week). Macron has converted Pécresse’s electorate, raising the question of the future of the Republicans, after having knocked out the PS in 2017. We can now discern the disappearance of these two traditional formations.

Decline in the working classes

The first round also shows Macron’s clear decline in the working classes and territories: in the cities of the working-class Parisian suburbs, for example, while the Macron still had good results there in 2017. In Seine Saint Denis, for example, which is the poorest metropolitan department, he went from 24.04% (his national score in 2017) to 20.27% in 2022 – while Jean-Luc Mélenchon went from 34% to 49.02%.

Marine Le Pen and Éric Zemmour: the far right on the rise

For five years, all polls predicted Le Pen would make it to the second round. A survey of September 2021 even placed her at the top of the youth vote. But the candidacy of Zemmour, more radical and more rooted in business circles, has shaken the Le Pen campaign. Nevertheless, even though from November until December some polls even predicted he would win 17% of votes, Zemmour eventually achieved 7% (which nevertheless puts him in 4th place).

It is therefore an interesting paradox that, despite divisions in this part of the political spectrum, one of the parties of the far right was able to reach the second round. As a whole, these parties mobilised 32.38% of votes (Zemmour, Le Pen, and Nicolas Dupont Aignan), a threshold they never crossed before – in no election at any time. Zemmour’s candidacy enabled Le Pen to complete her process of de-demonisation which she had begun in 2009, by appearing less dangerous and more credible, but in the meantime benefiting from a general focus on immigration and security, which Zemmour more vociferously represented.

Zemmour appeared more determined on the issues of immigration and Islam and less cautious than Le Pen. Nevertheless, it was parts of the RN’s traditional right and the upper classes who voted for him. The candidate owes his 7% to voters primarily to the pro-Le Pen qualified employees of previous elections, secondly to low-income former Fillon voters. Polarising the debate towards her themes, Le Pen simply did not need to campaign; she appeared on very few media platforms, and did not organise a large event to close her campaign.

Le Pen’s electorate remained relatively stable compared to 2017, although it expanded: she became very strong among the precarious (36% among workers), tending not to have an immigrant background, and among non-graduates (35%). She got only 12% of votes from executives. RN is becoming increasingly established throughout France. Even though Western France remained somewhat inaccessible to her, Le Pen was able to consolidate her position during the campaign. We observe significant transfers of the rural fraction of the Fillon electorate of 2017 in Western France. In the whole country, she is in first place in more than 20,000 out of 38,000 municipalities, achieving her best scores in small and rural communities.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon: the Popular Union?

The campaigns of the left candidates have been widely discussed in terms of the left’s division and internal wars; the Popular Union candidacy in the person of Mélenchon, seems to have succeeded in bringing together the different groups of the left at the ballot box. First of all, Mélenchon is the candidate who attracted the largest share of non-voters from 2017 (28%; closely followed by Le Pen: 25%). Socially, his highest scores are among the youth, workers (27%), and students (34%). Mélenchon also achieves very high scores (around 50%) in Overseas France, which represent France’s poorest départements, but also the most exposed to the climate catastrophe and particularly to the crucial issue of water resources. He also continues his breakthrough in the urban working class districts and among the Muslim community (70%). But Mélenchon has also mobilised the urban left, graduates, and parts of the skilled workers, as shown by his high results in multicultural neighbourhoods in large cities. Compared to 2017, he progressed overseas and in major cities.

The candidacy of Yannick Jadot (Greens) gathered 4.7% of voters. A green electorate that has not managed to develop beyond its traditional boundaries: young, highly educated (9% among those with more than 3 years of higher education, 1% among those without higher education), and living in cities. However, it would be incorrect to consider that Jadot’s electorate comes from the wealthiest classes; it consists mostly of people in positions requiring a degree but devalued economically (in the public sector: education, medical, etc.).

The candidate of the Communist Party (PCF), Fabien Roussel, received 2.3% of the votes. These small samples make analysis difficult, but not surprisingly, Roussel mobilised an older, middle-class electorate with lower education.

Second round

Faced with a close second round, the Macronists see in Mélenchon’s electoral base the keys to victory and are already beginning to position themselves on themes such as ecology and social issues.

Still, there is a real possibility Marine Le Pen will become president. She can rely on Zemmour’s voters – an electorate that has previously been inaccessible to her: the wealthy fraction of the classic right.

Mélenchon’s voters will be decisive for the outcome of the second round. He cautioned his voters not to vote for a far-right candidate. However, many may choose to abstain.

We recommend: