Since its ‘conversion’ to radical-right populism, Netanyahu’s Likud has remained in power for a decade, and following the third round of elections within one year as the dominant force in Israeli politics. Now it looks as if Likud will remain in power until the next election. How did they manage to become hegemonic?

In 2006, with a neo-conservative project, Likud, having only received 9 percent of votes, suffered its worst electoral performance since its inception in 1973. Netanyahu learned the lesson. Beginning in the mid-2000s, Likud muted into a radical-right populist party.

The radical-right populist historic bloc

Likud has led the constitution of a historic bloc with the ultra-Orthodox and nationalist religious parties, a political alliance that has merged three different social groups: the Mizrahi (Jews of Middle Eastern and North African origin), the lower-middle and middle classes, the nationalist religious sectors (primarily settlers in the Occupied Palestinian Territories), and the ultra-Orthodox. This historical bloc has been constituted around a radical right populist vision. As with all radical-right populist parties, Likud sees Israeli politics as a conflict between the (cultural) elites and ‘the people’, understanding the latter as an ethno-cultural unity, defined by the Orthodox religious view. Politics is presented as the perpetual conflict between foreign and internal enemies (Israeli Palestinians, asylum seekers, ‘leftist elites’: academia, the media, the juridical system, etc.) on one side, and the ‘true’ people on the other. On Election Day in 2015, Netanyahu called Jewish citizens to come to vote as ‘the Israeli Arabs are flocking to the polling stations in droves’. In March, he declared that the Arab Members of the Knesset (MK) ‘want to destroy the country’. The modification of the Basic Law in July 2018 – Israel as the ‘Nation-State of the Jewish People’ – gave constitutional status to the exclusion of the Palestinian minority. As is the case with all radical-right populist parties, Likud considers democracy to be the unmediated expression of the homogeneous will of the people, opposing this to central elements of liberal democracy such as judicial review; and is ready to limit human rights if they harm national interests. Thus, they have attacked human rights organisations and anti-occupation NGOs.

But a successful discourse cannot alone explain Likud’s success. In order to maintain the cohesion of this bloc, the right-wing coalition has combined populist exclusionary discourse with certain economic policies. From the mid-1980s, Israel had undergone significant changes in sectoral composition and in the distribution of power between capital and labour. Capital’s share of the national income has been rising constantly, and so has inequality among employees. However, since Likud’s return to power in 2009, Israel’s economic policy, though still within the limits of neoliberalism -has shifted. The minimum wage grew 37% and the median wage grew as well. The Gini index (expressing income inequality) went down from 0.5099 to 0.4585 (National Insurance Institute, 2019). These developments, together with a rise (of 62%) in household debt and a strong shekel, increased the consumption capacity of the lower-middle and middle classes. The strong shekel lowered the prices of imported goods, which in Israel represent a significant part of consumption. For a combination of these three reasons the rate of private consumption in Israel has increased more than the OECD average. The government also targeted the lower and middle classes through market-based policies, with measures including negative taxes, subsidies for after-school programmes, reduction of tariffs, and stimulation of individual saving. Moreover, housing prices were targeted by subsidising developers, and prices of items such as flights and cellular phone calls were lowered by increasing competition. Thus, in the last decade, the type of economic development, along with specific policies aimed at the lower middle and middle classes, provided the economic basis for the consolidation of a historic radical-right populist bloc. Moreover, the coalition continued to invest significant sums in settlements in the Occupied Palestinian territories, and in the ultra-Orthodox sector, thus ensuring the support of these two social groups that that are part of this historic bloc.

Liberalism as a failed alternative

The lack of a genuine political alternative also contributed to the populist radical right’s success. There have been two principal reasons for this: First, the political exclusion of the Arab Palestinian minority and the liberalism of the Israeli left. Just like the populist radical right, the liberal centrist and centre-left parties such as Blue and White and the Labour Party, also refused to consider government coalitions with the political representatives of the Arab Palestinian minority. The refusal to form a government coalition with the Joint List (the electoral coalition representing the Arab Palestinian minority) was a central element of the electoral campaign of the Blue and White party, a centrist force and Likud’s main electoral rival in the last three elections. Since the Arab Palestinian minority’s interests are clearly opposed to those of the populist radical right and they make up 21% of the population, its political exclusion severely constrains the constitution of an alternative hegemonic bloc. The second obstacle to an effective opposition is that in the Israeli context, the individualist and elitist character of centre and centre-left liberalism inhibits its appeal in the eyes of the popular classes that support Likud, in a society where traditional Jewish community identitarian values are very strong.

Though support for the rightist bloc remains constant, following the last elections the parties that opposed Netanyahu could have formed a minority government supported by the Joint List.

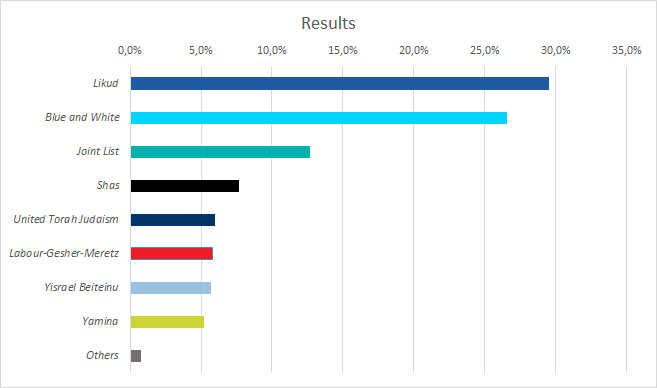

Results Elections 2 March 2020

Turnout: 71.5%

Source: https://votes23.bechirot.gov.il/

For a brief period, there was a window of opportunity for putting an end to Netanyahu’s reign. In order to avert this, Likud launched a racist campaign, claiming that a government supported by the Joint List represented a threat to Israel’s security. Then Netanyahu took advantage of the Covid-19 crisis to put pressure on Benny Gantz to join Likud in a coalition government, dividing Blue and White and dismantling the frail alliance of 61 members of parliament who supported him. While Netanyahu was able to maintain the cohesion of his historical bloc, Gantz provoked the division of his party, the dismantling of the frail 61 MK alliance, and the fragmentation of the social groups that opposed Likud’s hegemony.

The crisis and beyond

Netanyahu’s future success, however, depends on how Israeli society will exit the Covid-19 crisis. The public health system faces this dramatic situation after more than two decades of neoliberal policies. Those policies included a significant decrease in healthcare expenditure from public sources (currently around 60%, among the lowest within the OECD countries), budget cuts in the field of public health, and lack of investment in human and physical infrastructure. Aside from the public health crisis, Israel is facing a deep socio-economic crisis.

The central bank and the Ministry of Finance’s economic orthodoxy has resulted in late and insufficient responses. One million people are unemployed, and unemployment benefits are low. Support for the self-employed is even lower, and aid for small and medium enterprises is far from adequate. Thus the socio-economic consequences of the public health crisis may be dire, likely influencing the cohesion of the social bloc that supports Likud.

The crisis thus also presents an opportunity for progressive forces. The challenge is to build a social alliance built on a Jewish-Arab partnership. A partnership that puts forward an alternative hegemonic programme and discourse that addresses the causes of radical-right populism’s rise.