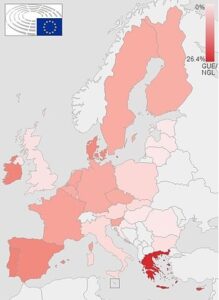

Jean-Luc Mélenchon came a very close third behind Marine Le Pen in the first round of the presidential election in France, Sinn Féin became the strongest party in Northern Ireland, and Syriza is preparing to re-enter the Greek government. Barbara Steiner gives an overview of the strength of left parties in Europe.

This article does not address the necessary left strategies, the influence of media and capital, changing social structures and modes of production, neo-colonial and gender relations, the epistemological crisis (i.e., the crisis of reason), the societal care crisis or the ecological catastrophe of our planet. These issues, along with the changing demands we put on parties and the question of whether the 150-year-old party form is still up to date, remain to be dealt with. But recent developments in the strength and governmental participation of left parties in Europe alone allow important conclusions to be drawn.

The French left achieved particularly significant success: Jean-Luc Mélenchon, candidate of the movement La France insoumise (LFI, “Insubordinate France”), led the left camp with 22% of the vote. However, he did not get into the run-off with Macron, not least because of the strong fragmentation of the left with seven candidates. In the election campaign, he courageously took the side of the racially oppressed and the side of peace and disarmament. He has a stable voter base among the poor, precarious, racially discriminated and young working classes. At the beginning of May, a left alliance was formed for the parliamentary elections in June. These are much less popular in France and more difficult to win because of the majority voting system. But under the name Nouvelle Union Populaire écologiste et sociale (NUPES), the LFI, the Greens, the CPF and the Socialists are joining forces in a historic alliance to provide the Prime Minister and to form an antipole to Macron in parliament. This is an important sign of unification for the left across Europe.

There seems to be an inverse connection between the strength of the left and that of social democracy in some countries: in France and Greece, the socialist parties have been almost erased and a strong left is taking their place. In Germany and Portugal, where social democracy regained strength, the left lost.

In his campaign for the early parliamentary elections in January, the socialist president of Portugal, António Costa, succeeded in demonising the left parties (the Left Bloc and Communist Party) that formerly supported his minority government. His attacks on the parties were much more aggressive than his attacks against the right. Support for both fell from 9.5% and 6.3% respectively to around 4.4%, and Costa can now govern with an absolute majority.

Here, the role of opinion polls and the media in influencing voters must also be criticised. They had wrongly predicted a neck-and-neck race between the centre parties. In addition, there was the threatening scenario of a far-right coalition taking over the government if the socialists did not win. In fact, there was no relevant migration of voters between the right and left camps. This means that, in contrast to many other European countries, there is still a left-wing majority in Portugal, with which the right was repelled.

Is government support fatal for radical left parties?

In Portugal, the period of 2015–2019 in which the left parties supported the government brought several reversals of neoliberal “reforms” of the Troika and various social improvements. After the 2019 election, Costa did not continue his agreement with the left, preferring to secure the support of various liberal MPs, as well as that of the right for some laws. For the radical left parties, with their demands for social and labour reforms, this course could only be harmful, and this was in line with the interests of employers’ associations.

In the Czech Republic, the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM) lost massively as a result of its support for the neoliberal and corrupt ANO government. They, along with the Social Democrats, failed to reach the 5% threshold and are no longer represented in parliament. After the transition, the KSČM was the only successor party to the communist parties of real socialism in Europe which still included communism in its name and also retained its place in parliament. As late as 2002, it was the third strongest force in parliament with 18.5%. But this result dropped in all subsequent elections to 7.8% in 2017. With this, it became the kingmaker of the minority government of the oligarch and founder of ANO, Andrej Babiš, which it supported by means of a tolerance agreement. This was possibly a mistake. Another problem is that for both members and voters of the KSČM the average age is very high, and the party has struggled to renew itself in terms of personnel. At least the party has now elected the young MEP Kateřina Konečná as its chairperson. Whether she can usher in a new political spring – after her confirmation as chairperson by the party congress in May – remains to be seen.

The left remains stably unstable

The Left Party in Germany almost suffered the same fate as the Czech Communist Party. Only thanks to three direct mandates did it remain in the Bundestag. Some of the reasons for this include a lack of strategy, internal party conflicts and being caught between the Greens and the Social Democrats. The Social Democratic Party advocated a minimum wage of 12 euros and the Left Party demanded one euro more but were not able to implement it. In addition, there were difficult strategic manoeuvres regarding other issues such as the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan. An urgently needed strategic discussion was started and bogged down by the ongoing Covid-19 crisis. The political strategy therefore remained unclear for many voters. The current debates seem to be directed inwards and the party does not seem to be on the offensive against a warmongering traffic light coalition government. In June, the party congress will take place in Erfurt, where many hopes of a new start lie.

In the Nordic countries, the left parties also support social democratic governments or – as in Finland – are involved in government and yet remain stable. But here, too, they are faced with the dilemma: participate in or support governments led by social democrats and share responsibility for their failures, or remain in opposition to them, thus depriving themselves of influence. Particularly on issues of militarisation and NATO, this poses great challenges to the parties. In Denmark, the Red–Green Alliance/Unity List achieved gains in the regional elections and even became the strongest force in Copenhagen. Nevertheless, they did not win the mayor’s seat from the other parties, which also shows how ultimately limited the influence of the voters’ will is on the distribution of power.

The left (back) in government?

The Cypriot Progressive Party of the Working People (AKEL) gained 22.3% in the 2021 parliamentary elections. From 2008 until 2013, the left party governed Cyprus.

In Spain, Unidas Podemos (UP) – the alliance of the United Left (communist party and other leftists) and Podemos – is part of the government led by the Socialists (PSOE), which also includes the Socialist Party of Catalonia. This government came into being in January 2020 after several rounds of elections, when the PSOE had practically no other choice. Only in this situation were the socialists prepared to govern with a leftist party and thus meet the demands of the electorate. For Unidas Podemos, this meant entering the government as a relatively weakened partner after Podemos’ spectacular rise in 2015. The most popular minister in this “progressive government” is the independent communist labour minister Yolanda Díaz. After a nail-biting event due to the weak parliamentary majority, she pushed a new labour law through parliament that strengthens collective bargaining rights. She could become the leader of the Unidas Podemos after Pablo Iglesias withdrew from party politics overnight in 2021.

New elections are looking increasingly likely in Greece this autumn. The conservative government is characterised by mismanagement, be it of the pandemic, forest fires or snow chaos. But even before that, regular election dates in Greece were rarely respected and maintained. Therefore, everyone is gearing up for new elections. In order to counter the conservative supremacy of Nea Dimokratia and the media, Alexis Tsipras and Syriza are planning a progressive alliance with all leftists, progressive forces and democrats. The ruling party from 2015–2019 failed to make gains from the health crisis and remains constant at around 27% in the polls. It held its third party congress in April – the first for six years due to Covid-19 – and continues to pursue the path to becoming a mass membership party. In his speech, party leader Tsipras presented a radical left reform policy programme.

After the election success in Northern Ireland it seems likely that socialist and nationalist Sinn Féin will win the elections and – should they enter government – possibly finally launch a referendum for a united Ireland.

In Slovenia, the green-liberal entrepreneur Robert Golob, who only became known to the wider public a few months before the election, won the election with his Freedom Movement as the main challenger to the ruling Janes Janša. The Levica party, founded in 2014, lost many votes to him, with support dropping by more than half and the party barely holding on to its parliamentary representation with 4.4%. Nevertheless, it is now part of Golob’s government together with the Social Democratic Party. Party leader Luka Mesec is deputy head of government and Levica holds three ministries.

Hungary and Serbia: No – and a new – left on the ballot paper

In Hungary, the unusually broad but neo-liberal opposition alliance from centre-left to right lost to Viktor Orbán at the beginning of April. Not least because of extremely high financial and organisational hurdles and blockades, there was no radical left party on the ballot.

In Serbia, the ruling Serbian Progressive Party managed to stay in power – thanks to a pyrrhic victory – and the left alliance Moramo (We Must) managed to enter parliament for the first time, winning 14 mandates in Belgrade.

Conclusion

The left can only grow through alliance. The communist left in the Czech Republic, Italy, Portugal and France, but also the renewed left in Germany and Portugal and the left project in Spain are on the decline in elections and polls. Small parties supporting social democratic governments cannot count on the support of these governments. A transformation of Europe into a social and ecological union can only succeed as part of a strong alliance of progressive forces.

We recommend:

- Radical in Diversity: Europe’s Left 2010-2020, edited by Cornelia Hildebrandt, Danai Koltsida and Amieke Bouma

- Meeting the Left. Webinar recordings on transform europe´s YouTube-Channel.

- In the Aftermath of the European Elections: The European Left Facing New Challenges. eDossier, transform! europe

See also:

The latest campaign of The Left in the European Parliament: Power to the People!

All around Europe people are standing up for their right to clean and affordable energy. The European Commission cannot keep defending the interests of a few powerful corporations. European leaders need to side with the demands and hopes of people and families for a fair, just and sustainable energy model.