In light of the far-reaching changes of power relations within the EU, the left requires new strategies. An analysis.

From now on the radical left will be the smallest faction in the European Parliament. At 5.46% the left reaches a voter approval similar to the one at the end of the 1980s, with the only difference being the current conditions of a distinct swing to the right. In Spain, France, Germany, in particular, the left parties remained far behind their expectations. Compared to 2014, the radical left lost about 20% of their mandates.

Within the faction of the radical left the Spanish Unidos Podemos and the Greek Syriza are the strongest parties with six representatives each. The German DIE LINKE sends five mandataries to the European Parliament (EP). In addition to that, there will be one representative of the Animal Rights Party from Germany. With two seats each the Portuguese Bloco and the Left-Green Alliance (including Communists), Sinn Féin and AKEL from Cyprus are represented. One seat is held by the Swedish Vänsterpartiet, the Danish Unity List-RGA, the Finnish Left Party and the Belgian Workers’ Party PTB-PVDA respectively. The same is true for the Czech KSČM, who, however, has also lost influence. No longer represented in the EP is the Italian left, who made it to the European Parliament with the List Another Europe with Tsipras in 2014. The Slovenian Levica did not succeed, in spite of gaining 6.3% of voter approval. If Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise (LFI) will join the faction with their six representatives is yet uncertain.

Find here our post-election country analyses;

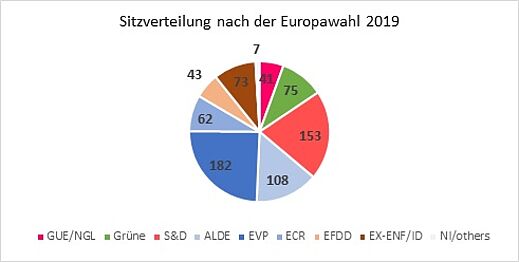

Conservatives and Social Democrats have lost 20%[1] of their mandates each, but still remain the strongest factions with the Conservatives holding 182, the Social Democrats 153 seats.

With the Greens and the Liberals two explicitly pro-EU party families are the winners. The Greens now have 75, the Liberals – thanks to Macron’s decision to join this faction – hold 108 seats. The right-wing parties of the European Conservatives and Reformers (ECR), the even further right-wing faction of Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD) and the newly-founded faction of Identity and Democracy (ID) gain 178 seats altogether, but the final formation of the right-wing factions will only show after the Brexit is in effect. If we add more parties, such as FIDESZ, they rely on 25% of the voters.

This means that, beside the Conservatives and Social Democrats / Socialists, the EP will consist of a pro-EU-bloc of Greens and Liberals, together amounting to about 25%, and a strong nationalist-oriented anti-EU right-wing bloc. Still, these election results show that the parties of the right did not become as strong as they had hoped for. Still, there is in the EP a clear right-wing slant which is more than the mere increase in votes of 22% in 2014 to 25% in 2019, especially if we take into account the impact of the right-wing parties in the national governments and via the European Council. The political right is in government or forms part of government in Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy and Poland. In Italy and France, Salvini’s Lega and Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN) became the strongest parties in the European elections. And, by shifting the agenda they have already been influencing national and European politics for quite some time now.

At the same time, the increase in votes for the Liberals and the Greens are increases of votes for clear pro-EU-positions and a consolidation of EU-politics. This is of some significance if we consider the Brexit-paradox. On the one hand, in the face of the chaos created by the Brexit, almost all parties – no matter what their political orientation – moved away from their anti-EU-position, more precisely, from their exit-positions during their election campaigns. On the other hand, the Brexit-party became the strongest party in Great Britain with more than 30% of votes.

EU-wide, the voter turnout amounted to 50.93%, which is significantly higher than in 2014 when the voter turnout was 43.09%, whereby the differences are traditionally very great between Slovakia with a voter turnout of 22.74%, Portugal with a voter turnout of 31,40% on the one hand, and Spain with 60% and those countries with compulsory voting with a voter turnout of 80% and more, on the other. There is a significant rise of voter turnout (more than 10%) in the Czech Republic (28.72%), Germany (61.41%), Hungary (43,36%), Romania (51.07%) and Spain (64.30%).

Distribution of Seats in the New European Parliament

source: https://election-results.eu/european-results/2019-2024/;

GUE/NGL: European United Left/ Nordic Green Left (radical left); S&D: Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (social democrats); ALDE: Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (liberals); EPP: European People’s Party (conservative); ECR: European Conservatives and Reformists (right wing); EFDD: Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (right wing), ID: Identity and Democracy (right wing); NI: non-affiliated;

A Change in Power Relations

Within the next weeks and months we will see an intensified struggle about the question of shaping the future EU, of its consolidation, the creation of new EU-institutions and instruments or about the dismantling of the EU-institutions, a shift of competences to the level of national governments going as far as the breach of European treaties and directives even at the expense of the threat of sanctions. The right will fight this struggle mostly in those areas that further question the democratic character of the EU, weakening human rights positions and their real enforcement. The contradictions arising between the factions and the ruling blocs must be examined in further analyses, as must be the cracks within and between the ruling blocs.

If we assess the power relations of the individual fractions with a view to possible majority ratios regarding the election of the President of the EU-Commission, among others, it becomes obvious that both large factions, the Conservatives and the Social Democrats, at 44% can no longer act as an informal ‘grand coalition’. That means, the EPP and S&D will not have enough votes to elect the President of the European Commission (and, later, the President of the ECB). Under these circumstances, finding a majority without resorting to either the Euro-sceptical faction of the ECR or both right-wing factions (ID and EFDD) requires an inclusion either of the Greens or the Liberals and an opening-up of offers with regard to topics, structures or personnel. Since neither Macron nor the Greens have, so far, signalled their support for Manfred Weber, another problem becomes obvious. Within both factions the representatives of Germany, Italy and France are losing importance. However, it is not clear yet to what degree this will have political effects.

For the Conservatives and Social Democrats the changed situation means that they need to find partners. A coalition between Conservatives and the right bloc, possible in theory, also does not have a majority within the EP.

Thus, if Conservatives and Social Democrats want to find a majority without the right bloc, they have three possibilities:

a) forming a ‘liberal great coalition’ together with the Liberals, who, on principle, stand for a continuation of the previous policies and a consolidation of the EU at the same time – both in dispute with the parties of the right. Although refraining from a fundamental political change, this project would at least mean an intensification of the process of EU-integration and cooperation in the areas of economic and foreign policies, or

b) forming a ‘green great coalition’ together with the strengthened Greens. In such a constellation there is the chance of developing either a social-green or a neoliberal-green project as a European ‘driving force’ for ‘green’ capitalism. To which degree this ‘motor’ can be shaped to become one of social-ecological transformation will significantly depend on the strength and direction of social democratic/socialist parties and on the strength of a radical left with the capacity to mobilise and assert itself on a European level.

c) Of course, there is also the chance of acting with changing majorities. Such an approach enables the Conservatives to by and large maintain the status quo with necessary green adaptations and partial consolidation of the EU with regard to foreign, climate, peace and security policies – in the end also the Greens stand for a militant defence of European values.

Results of the European elections at a glance;

source: data of European Parliament, own compilation;

About the Left

If we look at the left side of the party spectrum, the parties of the left, the Social Democrats, the Socialists and the Greens taken together only account for just short of 35 %. The weakest element in this part of the political spectrum is the radical left.

Election Results

|

|

GUE/ |

Greens |

S&D |

ALDE |

EPP |

ECR |

EFDD |

ENF/ |

INDPT |

|

2019 in % |

5.46 |

9.99 |

20.37 |

14.38 |

24.23 |

8.26 |

5.73 |

9.72 |

0.93 |

|

2019 seats |

41 |

75

|

153 |

108 |

182 |

62 |

43 |

75 |

7 |

|

2014 |

6.92 |

6.66 |

25.43 |

8.92 |

29.43 |

9.32 |

6.39 |

– |

6.92 |

|

Diff. |

-1.46 |

+3.33 |

-5.06 |

+5.46 |

-5.2 |

-1.06 |

-0.66 |

– |

-5.99 |

|

2014 seats |

52 |

50 |

191 |

69 |

221 |

70 |

48 |

0 |

52 |

|

Diff. |

-11 |

+25 |

-38 |

+41 |

-39 |

-8* |

-5 |

75 |

-45 |

source: European Parliament;

*Note: When allocating the seats of ECR, EFDD and ENF, we must take into account that some mandataries of these parties moved between these factions. For this reason it makes more sense to work with the overall number of mandates of these factions, i.e., ECR+EFDD 2014 = 118, ECR+EFDD+ENF/ID 2019 = 178;

The parties of the radical left of the hitherto confederal faction of the United European Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) could only win 5.46% support and will have 41 representatives in the EP, if La France Insoumise joins the faction. Should the negotiations between the national delegations fail, the split of the left that was obvious in the election campaign will be continued on the EP-parliamentary level and this in the face of a weakened left, whose voter potential has, with a few exceptions, not been higher than 5% since 1989. This means that since the collapse of state socialism, left parties have not succeeded to overcome their defensive position. At the same time, the conditions for the assertion of left politics have worsened with the shift to the right within the EU and the weakness of the social democratic/ socialist parties, in spite of successes of individual parties. With the end of the post-war period also the Western European Communist parties have now lost their social significance and relevance as important forces in the struggle against National Socialism, Fascism and war.

The Greek branch (MeRA25) of the alliance of DiEM25 winning 2.99% of the votes did not succeed in getting into the EP, failing to negotiate the three-percent threshold. Yanis Varoufakis ran in Germany and could obtain 130,072 votes, i.e., 0.3%, in Greece he received 140,000 votes – not enough for getting into the EP. However, it is also possible that this case indicates a more fundamental problem regarding the implementation and legitimation of transnational lists. At least the path Varoufakis pursued by forming such a list in competition with the LINKE did not lead anywhere, in spite of the fact that the top candidate was well-known.

In addition to the weakened position of the left, it must be noted that also any new faction of GUE/NGL can be formed only under the condition of a federal structure, since positions regarding the role of the left in the EP, the understanding of politics, the strategy and organisation as well as specific topics differ widely. Another aspect is that any Europe-oriented strategy development is complicated further by the dominance of nationally oriented left political approaches and their prolongation onto the European level. Thus, working for a common agenda of the federal faction is often possible only for specific questions, in particular, the social question or the issue of international trade agreements (TTIP). The requirement of speaking with one voice contradicts the federal character of the faction.

In order to understand the extent of the changes even better, we will cast a glance at the losses and gains. Compared to 2014, the losses of 11 seats for the left, 38 seats for the Social Democrats and 39 seats for the Conservatives are equivalent to a loss of 20% of their former voters respectively in the core countries of the EU. Quite different the situation for the Greens and the Liberals: For the Greens the gain of 25 seats reflects an increase of mandates by 50%, while the Liberals could more than double their number of seats.

Losses and gains in mandates 2019 as compared to 2014

source: https://election-results.eu/european-results/2019-2024/, own compilation;

Share of the votes at European elections of the fractions GUE/NGL, Social Democrats/Socialists, Green, Liberals and Conservatives between 1979 and 2019

|

Faction in the EP |

Share of the vote 1979 |

Share of the vote 1984 |

Share of the vote 1989 |

Share of the vote 1994 |

Share of the vote 1999 |

Share of the vote 2004 |

Share of the vote 2009 |

Share of the vote 2014 |

Share of the vote 2019 |

|

GUE/ |

10.7 |

9.4 |

5.4 GUE |

4.9 |

6.7 |

5.60 |

4.76 |

6.92 |

5.46 |

|

S&D |

27.3 |

30.0 |

34.7 |

34.9 |

28.8 |

27.30 |

25.00 |

25.43 |

20.37 |

|

Greens/ |

– |

4.6 |

5.8 Gr. |

4.1 |

7.7 |

5.80 |

7.47 |

6.66 |

9.99 |

|

ALDE |

9.8 |

7.1 |

9.5 |

7.8 |

8.0 |

12.00 |

11.41 |

8.92 |

14.38 |

|

EPP |

26.3 |

25.3 |

23.4 |

27.5 |

37.2 |

36.70 |

36.01 |

29.43 |

24.23 |

source: Wikipedia/ own calculation and own compilation;

What has changed compared to 2014?

Among the continuities there is the ongoing trend of decreasing loyalties to the former major parties: both Social Democratic/ Socialist and Conservative parties are significantly and systematically losing both voter loyalty and political consent. While in the European elections of 1994 they still reached just about 35% of the voters, it is only about 20% today. In the year 2019 the Conservative parties are on the same level as in 1989.

For the first time since the beginning of European elections in 1979, both major parties together remain under 50%. That is, they must, in order to secure the required majorities, approach other party families. If they want to do so without resorting to the right-wing parties and factions in the EP, they need to win the support of the Greens or the Liberals. Thus, both pro-European party families could contribute to a modernisation of the EU-institutions and a moderate change in politics resulting in: green modernisation, liberal consolidation of the EU and strengthening the EU law as well as increasing the impact of EU-institutions on national policies and the creation of new instruments. They will have to do so in an atmosphere of permanent conflict with the political right so that we have to count with exacerbated crises, even blockades.

The results of the European elections of 2014 are an indicator of political polarisation: in the core countries and in the Northern EU-countries, the protest against the dominant policies flocked to the right, favouring right-wing populist and right-wing conservative parties. In the Southern European countries, especially in Greece, Spain and Portugal the protest strengthened the left, and even in Italy the force of the protest was strong enough for the left to re-enter the EP thanks to the List Another Europe with Tsipras. In 2019 this polarisation does no longer exist. Not only in the Northern, but also in the Southern and Central-Eastern European countries of the EU the protest has led to the formation of new right-wing parties, who partly had not yet existed in 2014, and to the increase in votes of the right-wing parties in the 2019 European elections. League is no longer the Northern League, it became the strongest force in all of Italy, with the European elections reversing the national power relations. At the same time and unlike the right, that is steadily gaining voter approval thus solidifying its power, the development of the left is stagnating.

The results of the 2019 European elections reveal a new polarisation between the party families not any more along the conflict lines drawn by the austerity and social policies but regarding the question of consolidation vs. dismantling of the EU even to a mere free trade zone; of an EU tackling questions of the future and taking up green and digital issues vs. an EU adhering to traditions and favouring stronger possibilities of intervention by national governments and parliaments.

The parties of the radical left clearly lagged behind expectations. A trend towards a reversal of at times high poll ratings in favour of the left in Spain and France has been confirmed. Unlike in 2014, the parties of the radical left could not agree on a top candidate but entered the election campaign divided. Three European projects competing against each other: Maintenant le Peuple (MLP), DiEM25 and the European Left Party (EL) all suffered a defeat. Since all party projects, quite diverse with regard to their origin, view of politics and organisational matters, strategy and focus of their campaigns have lost, it is difficult to give simple answers. Yet, it is sure that none of them succeeded in adapting to the newly evolved political situation and the emerging new dimensions of conflict, tackling them with a common strategy and, most of all, with a European perspective.

Between 2014 and 2019 the change of conflict lines in Europe took place also before the background of a global situation itself undergoing a profound change. In the face of these developments and the open view of the Brexit chaos popular consent to the EU was extraordinarily high.

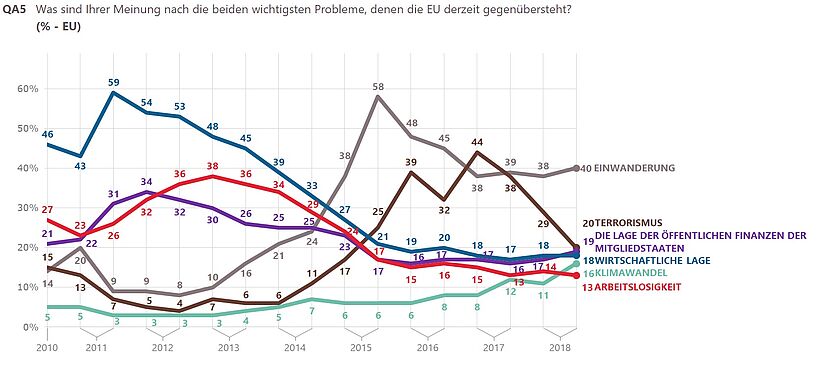

The November 2018 Eurobarometer-data reveal the following developments: In the years of 2011/2012 – the time of the strongest mobilisations of social movements against EU austerity policies – up to 2014 unemployment and public finances were considered to be the most important challenges at the European level, especially in Spain, Portugal and Greece. This conflict constellation helped the success of the left in 2014. After 2015 the focus of the major tasks of the EU has shifted, first towards the question of how to deal with terrorism and immigration. Clearly less in focus than in 2014 were the problems of unemployment, the economic situation within the EU and state finances. The change in importance of climate change showed itself as a rising but not yet polarising dimension of conflict.

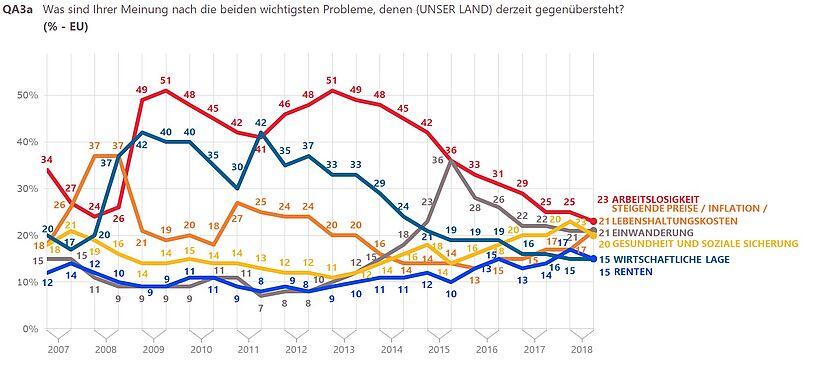

Answers to the question of what was important to tackle on the national level in the countries of the EU reveal a similar picture: in 2014 the problems of economic development, unemployment and public finances were dominant at the national level. At the end of 2018 people perceived a bunch of different topics that required being dealt with: unemployment, rising prices and inflation, migration, the economic situation and pensions. At the end of 2018 there were no prominent polarising topics with the exception of the question of migration. At that time Eurobarometer does not yet list the climate crisis among the tasks to be dealt with on a national level, although the issue had been present in individual countries for quite some time by then. Contrary to this, climate protection gains in weight as a task to be dealt with on a European level.

In the beginning of 2019 the economy, finances, unemployment, climate and environment were almost equally seen as the most important topics to be dealt with on the European level – the situation is still open! At the same time, there was already a trend indicating that the climate issue could become a new polarising issue. It will depend on the power of the left, if this ecological trend will also be defined as social.

Most important tasks of the EU

source: Standard-Eurobarometer 90, Autumn 2018, p. 13;

source: Standard-Eurobarometer 90, Autumn 2018, p. 13;

40: migration, 20: terrorism, 19: finances, 18: economy, 16: climate change, 13: unemployment;

Most important tasks of own national country

source: Standard-Eurobarometer 90, Autumn 2018, p. 17;

source: Standard-Eurobarometer 90, Autumn 2018, p. 17;

23: unemployment, 21: rising prices, inflation, cost of living, 21: migration, 20: health and health insurance, 15: economic situation, 15: pensions;

What is the importance of these elections and what is their importance for the left? Summarising conclusions

1. The shift to the Right described above goes on under the conditions of the previous mainstream parties becoming weaker. This shift to the right of policies already now manifests itself at the European level in questions of migration and refugee policies, in particular, when it comes to securing the borders. One example of this development is the cancellation of the European sea rescue programme Sophia that had been adopted primarily by Conservatives and Social Democrats.The declared aim of changing the EU and their instruments is becoming part of the fiercest conflicts. The question of which institutions will have which competences in the future will become a crucial one. That means that it will not only be about policy-making processes, i.e. concrete topics, but also about questions concerning the treaties and institutions which will become the subjects of conflict more often.

2. The Greens could win, because they seem most trustworthy and competent when it comes to dealing with questions of the future. This concerns climate issues but also issues of digitalisation – in particular, the critique of the copyright law with the possibility of installing upload filters, a topic that was discussed and negotiated on both national and European levels. It also concerns the protection of the environment such as the handling of glyphosate. Regarding all these topics the Greens were accessible and capable of dialogue at the European level, especially so in France, Germany and the Netherlands. In doing so, the Greens could use their openness for new topics, their image of being an advocate for the protection of the environment and the climate. Certainly, the left also had the protection of the environment and the climate on their agenda, to be seen, among others, in the Climate Manifesto of GUE/NGL published shortly before the elections. But it was much too short-term in order for the left to be considered a credible advocate for this topic. The election platform of the EL mentioned the topic without developing it any further. The ideas of the LFI election programme did not on time become part of a European left discourse on the environment and the climate.

3. A European left must stand for a social and ecological agenda and transformation. In doing so, we must, however, not adopt concepts developed by others. We must develop independently our agenda and do so together with social movements, initiatives and other civil society actors and feed work done previously into an inner process of discussion among the left. However, this requires new and open spaces for broadest possible left discourses and alliances. The social question will be here of special significance. During the election campaign, however, one could not see the actual practical value of the left regarding this topic area.

In view of this result, the left not only has to accept our obvious defeat, but we also have to ask ourselves what the reasons were for this defeat. There are no simple answers. It is not the case that one of clearly identifiable strategies or type of party of the radical left has lost, but all. The only exceptions which deserve to be studied closer are the Portuguese Left Bloc and the Walloon Workers’ Party (PTB). Notably, parties that have lost are Podemos, La France Insoumise, DIE LINKE, Syriza and KSČM. The background to these concrete examples of defeat are completely different political conditions, varying concrete national conflict situations and political cultures of different organisations. However, the question that needs to be answered is if there are any common structural and strategic causes, i.e., if we need new forms of strategic cooperation towards the development of a joint European strategy and agenda. The majority of the left has been conducting national campaigns for these European elections, which must be seen against the background of their relative strength on the national vis-à-vis their weakness on the European level. But only very few have won anything that way. That is how the European Left is losing its practical value.

4. As the left we have to deal with our political methods, the forms of our politics, among others with the question why we do not succeed in tackling changed conflict situations in dynamic times of changing mobilisations. We must raise the question of the function of a 5%-party in the EP and what it would have to achieve in view of the challenges. It must ask itself these questions on both national and European levels.

—————

[1] All subsequent figures refer to those provided on the website https://election-results.eu/ from June 26th, retrieved on June 27th, 2019.