In times of the coronavirus – just as in the 2008 financial crisis – the national state is again a central actor in Europe. Financial policy remains tied to the economic pecking order, with Germany at the very top. ‘Eurobonds’ are the key area of contention.

The coronavirus is going around. Television programmes, newspapers, and alternative media are filled with it. Among the most widespread assumptions is the notion that the spread of the virus is mainly determined by individual factors. Clearly, this is not so. What is decisive is the access the sick have to the health systems. Here there is a stark difference between EU Europe and the global South. But there is also a difference inside the EU. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO) from mid-April, the pandemic’s death toll in Italy was 203 dead per million inhabitants, in Spain even 339, and in Germany merely 31.

The capacity of German’s health system is proudly emphasised. Here neoliberal cutbacks had clearly been made in previous decades, but not so drastically as in the southern countries after the 2008+ financial crisis. Spain’s Foreign Minister Arancha Gonzáles Laya recently stressed that her country too had ‘previously had a solid healthcare system, but it has less capacity today than it could have had’. In Greece the Troika’s cutbacks during the debt crisis put the country’s healthcare system into a completely ruinous condition – over 20,000 doctors have emigrated since 2010. Nevertheless, up to mid-April, through very early and very drastic restrictions, the government managed to limit Covid-19 mortalities to ‘only’ 12.5 per million inhabitants. However, the country has to deal with far-reaching economic consequences. Tourism has collapsed worldwide – in Greece 30 per cent of the country’s economic output depends on this sector.

Against this background the idea of ‘Eurobonds’ has resurfaced – together with European government bonds – now called ‘coronabonds’. The opposing fronts within the Eurozone remain: the Southern countries, above all Italy and Spain – supported by France – are pressing for the creation of this instrument, and Germany, assisted principally by the Netherlands and Austria, rejects it. It is true that Germany’s Finance Minister Olaf Scholz (SPD) concedes that the former main argument for rejecting Eurobonds – that these would slow the southern countries’ ‘reform drive’, in other words, that they themselves are to blame for their financial misery – does not apply here since ultimately no one is responsible for the corona pandemic. Nevertheless, ‘coronabonds’ would be a ‘communitisation of debts’, something for which the EU Treaties do not provide, and so, in Scholz’s reasoning, other credit-financed forms must be found to financially cushion the economic consequences of the coronavirus.

Germany and the EU – the pre-corona situation

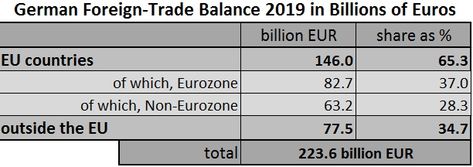

Germany’s foreign-trade turnover in 2019 reached a volume of over 2.4 trillion euros; exports lay at 1,327.6 billion, the export surplus at 223.6 billion euros, the current-account surplus at 266.2 billion.

The value of German exports to other EU countries in 2019 was 773.3 billion euros; here the surplus amounted to 146.0 billion euros. Exports at a value of 491.8 billion euros went to the Eurozone countries, with a surplus of 82.7 billion euros. This means that in 2019 65.3% of German export surpluses came from the EU and 37.0% from the Eurozone.

Source: German Federal Statistical Office, Press release No. 039 of 7 February 2020, own modification

Note: Due to the rounding, some differences may exist between subcomponents and the total sum;

In 2010, 79.0% of the export surpluses came from exports to other EU countries and 55.2% to the Eurozone. In 2019 exports to countries outside the EU were at a value of 550.3 billion euros with a surplus of 77.5 billion euros. This means that an increasing part of Germany’s foreign-trade surplus comes from its exchange with the world at large. Thus in the short space of nine years the EU and the Euro, rather than just being the principal source of German surpluses, are instead the basis and precondition of Germany’s global economic interests.

Internal tensions

German export surpluses are the flipside of the debts of other EU countries. ‘Austerity policy’ directed at the debtor countries resulted from the decision to uphold the Euro as the second world currency in competition and conflict with the US dollar. Inasmuch as the Euro is the basis of Germany’s position in the global economy, Germany policy prioritised saving and stabilising the Euro even if this occurred to the detriment of other EU countries, their social conditions, and stability. With this a relationship of tension emerged between global German interests as a geo-economic power and what is required for shaping the European Union as an integrated unit of states, peoples, and regions. From the viewpoint of integration goals, the disparities in development within the Union need to be reduced, while for Germany’s global interests they are irrelevant as long as they do not harm Germany’s export economy.

The Euro is frequently regarded as a core problem of the current tensions within the EU because the other EU countries cannot deploy currency devaluation, aimed at improving the price competitiveness of their national economies, to compensate for their trade and current-account deficits within the Eurozone. Thus during the 2008+ financial crisis euro-exit scenarios were discussed in various countries. Nevertheless, Donald Trump is right when he says that, with the Euro, the currency for Germany’s export economy is undervalued. The Deutsche Mark was an expression of the performance capacity of the German economy; the Euro’s value results, by way of international comparison, from the average of the performance capacity of all Eurozone countries, from Estonia and Greece to Germany, the Netherlands, and Austria. For this reason Germany’s export economy actually benefits from the lowering of the international purchasing price of the Euro brought about by the presence of the weaker Eurozone economies. At the high point of the Euro Crisis there was general agreement that although a collapse of the monetary union and a return to the D-Mark would not permanently damage Germany’s export economy it would lead to a hefty appreciation of the D-Mark and thus to a strong drop in exports (Wirtschaftswoche, 29 May 2012). Since then there has been no reason to alter this supposition.

Interlocked interests

The Federal Republic of Germany’s economy had, with its successful reconstruction after the Second World War, already become ‘Western Europe’s centre of accumulation’ in the 1950s, (Fülberth 2012, 39). At the end of the 1970s the European Monetary System (EMS) was created. It was characterised by a system of fixed exchange rates, which, however, were adaptable within certain ranges (‘currency snakes’); this was to facilitate the traffic of goods, services, and capital, and prepare a currency union. In view of the strengths of the Federal German economy within the then EMS, this was nevertheless a system in which the other countries were tied to the reference-currency country, as the Bretton Woods System had tied the world economy to the US dollar. Since the German Bundesbank was able to run its own monetary policy, mostly without heeding the concerns of the others, the idea arose, despite the continued existence of national states within the EU, of introducing the Euro as a common currency. The European Central Bank (ECB) was to make it possible for all participating countries also to co-determine monetary policy. The German condition, however, was that the ECB should be an independent institution on the model of the Bundesbank, that is, one that is decoupled from the fiscal policy of the Euro countries, and that combating inflation be declared as the priority objective. Much of what has been discussed since 2008 as a ‘structural defect of the Euro’ since 2008 is due to the political and economic construction of the EU.

The economic imbalances within the EU and the Eurozone are not the results of the introduction of the Euro but pre-dated it. However, they were aggravated by its introduction. Already in the three decades before the 2008 crisis there had been the ‘development of an asymmetrical division of labour between two different forms of accumulation regime’.

‘Germany formed the core of a group of actively extrovert economies. German extroversion was characterised by a strong industrial export orientation and an increasing involvement in financialisation processes abroad by means of capital export. For example, the Benelux countries and the Austrian economy were directly integrated into the German productive system’ (Becker/Jäger 2013: 170).

Since the 1990s, Eastern European countries were added as the ‘extended workbenches’ of German industry or as specific spheres of influence of this core group.

On the other hand, in the EU’s Western and Southern periphery, especially in Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and Greece, various forms of import-oriented and financialised accumulation patterns’ prevailed. Through the Euro these countries were deprived of the possibility of dealing with their deficits through devaluation.

‘In turn, they had the possibility of indebting themselves at lower interest rates. In Southern Europe deindustrialisation processes were consolidated by the monetary union, processes which had already been underway with the removal of opportunities to protect their industrial policy in the framework of EU accession in the 1980s. In the then new Southern European EU Member States capital accumulation shifted to tourism, real estate, and the construction sector. Capital groups in part moved their activities from industrial production to import.‘

The result was:

‘In Southern Europe and parts of Eastern Europe the trade and current-account deficits rose sharply. They were financed by loans from the Western European countries’ (Becker/Jäger 2013: 170).

Credit-financed consumption in the South and the revenues from exports reaped by Germany or the other core countries were the results of a reciprocal interlocking of interests, a mutually beneficial business transaction. Germany did not force this model on the other countries; rather the capital owners in the peripheral countries profited greatly from this and became agents of the model’s implementation – they became, so to say, compradors of Germany’s global economic interests. The crisis after 2008 revealed with increasing clarity the wide gaps between the centre and the various countries of the periphery, between the two accumulation models. At the same time the position of wage dependents and of the welfare state was weakened at the European level.

Widening inequality

Inequality in EU countries has visibly increased since 2008. And with this the bases of integration have eroded. Uniting EU-Europe by means of currency, without simultaneously creating a social union and environmental union, has proved extremely problematic. Germany’s foreign-trade surpluses within the EU contrast with the indebtedness of many other countries. The rule also holds with the Union that at the end the balance has to be zero, that is, every surplus on one side presupposes a deficit on the other side. The asymmetrical growth has largely brought economic development in the EU’s Southern countries to a standstill. With the introduction of the Euro the belief prevailed that it would afford protection from the impositions of globalisation. In reality it has aggravated the problems; the deindustrialisation processes are irreversible in the foreseeable future. The internal market as such leads in general to the de-industrialisation of the periphery to the benefit of the centre, where above all Germany is located. The high unemployment, especially youth unemployment, in the Southern countries, on the one hand, and the low unemployment in Germany , on the other, are its social and economic expression. In March 2019 the unemployment rate in Greece was 18.5%, in Spain 14.0%, in Italy 10.2%, in France 8.8%, and in the EU as a whole 6.4%. By contrast, in Germany it was only 3.2% (statista.com).

The corona crisis will further exacerbate all these problems – apart from the direct consequences of the pandemic about whose development and future victims no one can say anything certain now.

Already by the beginning of April 2020 Germany’s national (federal and state) aid package responding to corona amounted to 1.8 trillion euros. German government securities now have an interest rate of 0%; they are classified at the highest level – AAA – by US rating agencies. By contrast, Italy’s were just recently rated as ‘junk’. This means that any borrowing under coronavirus conditions here has to be paid for with high interest rates. All EU countries are now trying to put together aid packages – each country for itself. The EU Commission and the heads of state and government are, it is true, announcing their intention to initiate common measures, but ultimately everything is staying within national frameworks. In Italy state debt will rise to 160% of GDP. Therefore Italy, Spain, and France are proposing joint bonds. Germany rejects this, once again supported, as during the Euro Crisis, by the Netherlands and Austria. Their accusation is that this would mean ‘communitisation of debts’. If Germany demanded ‘solidarity’ in the refugee crisis, now solidarity is once again being refused. Thus Eric Gujer, editor-in-chief of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (3 April 2020) noted, ‘Germany wants to be Europe’s leading power but is behaving like its chief accountant.’

One of the EU’s maladies is called German hegemony.

——————————————————————————————————————-

Literature

Joachim Becker and Johannes Jäger, Regulationstheorie und Vergleichende Kapitalismusforschung: Die Europäische Union in der Wirtschaftskrise, in: Ian Bruff et al., Vergleichende Kapitalismusforschung: Stand, Perspektiven, Kritik, Münster: Verlag Westfälisches Dampfboot, 2013.

Georg Fülberth, Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Cologne: PapyRossa, 2012.