This is the first of a new transform! series of quarterly papers. They present the key points of social and economic evolutions in Europe and highlight the new contradictions caused by these evolutions on the political and ideological levels.

In June 2014, the World Bank lowered its prognosis for global growth from 3.2% to 2.8%, and for US-American growth from 2.8% to 2.1%. Following a period of poor economic growth in the first quarter, the IMF expects the USA to grow by only 1.7% this year, even though growth of 2% was previously expected. Developments confirm that there can indeed be no talk of a global economic upturn. Furthermore, both the USA and the EU have been boasting fragile growth rates which suggest that all developed capitalist countries are following the Japanese model: due to their continuous tendency to reduce their debt, they are unable to exit a period of stagnation marked by deflation. But what does stagnation or even contraction mean? Since the political elite continue to doggedly defend the existing distribution of wealth and power, the result is a constantly widening social gap.

The facts:

Firstly: US-American growth continues to be sluggish. According to the Beige Book, a report on the economy published by the Federal Reserve, the US economy’s slow recovery process continued during the summer months. The economy has grown in all regions of the country; expenditure within the tourism, automobile and the retail sectors have been the main drivers. The Federal Reserve called the growth rate “slow to moderate”. Equally, the labour market has improved in all parts of the country, the report states. For the housing sector, the report paints a mixed picture – this is also the reason why the IMF reduced its prognosis for the US growth rate once more.

For US-American developments, the Federal Reserve’s future policies are crucial. With regards to low price levels and a drop in unemployment, the Federal Reserve has reacquired government bonds and debt securities via real estate investments. Currently, the third purchasing programme for US government bonds (and mortgages) is in its final stage. Only USD 15 bn have been purchased on the market in the periods between the regular meetings of Federal Reserve agents. At the next conference of the FED’s steering committee in monetary matters, this sum will be further reduced to USD 5 bn – and it should be collected in full by the October conference at the latest.

In particular, developments on the US labour market (which is strong on paper) should have long ago triggered a response by the FED regarding interest rates, since the national unemployment rate has been reduced to 6.2% and is thus significantly below the goal of 6.5% defined as “crucial” by the former FED boss Bernanke.

However, for some time now the US labour market’s structure has been such that there can be no talk of a satisfactory labour market situation in the USA; the number of long-term unemployed and part-time workers remains too high. The labour force participation rate has been dropping steadily since 2000 and fell even more sharply after the last recession. Before peaking at the turn of the millennium, the participation rate had been rising steadily.

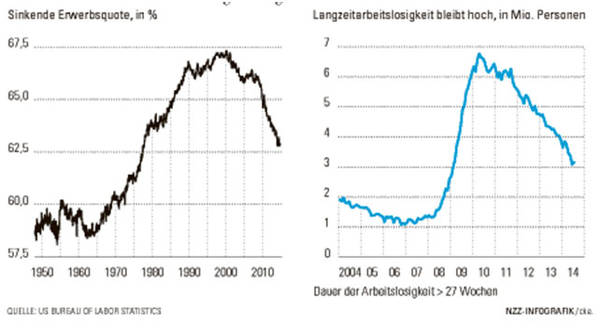

Fig. 1: Labour force participation rate and long-term unemployment in the USA

Decreasing labour force participation rate, in % Long-term unemployment rate remains high, in million persons

Source: US Bureau for Labor Statistics / NZZ.ch Period of unemployment > 27 weeks

Over the past months, the labour force participation rate has, in fact, levelled out just below 63%. However, this rate is still 3% below the level seen at the beginning of the recession. In fact, it had long been expected that this rate would start rising again together with the onset of economic recovery (with the US recession officially ending in 2009); when there is an economic upturn, workers previously laid off are re-employed and unemployed people are encouraged to look for jobs.

Explanations for why this has not happened and the factors behind changes in the labour force participation rate are the subjects of heated debates in the USA. The answer to this question is of particular importance, and also the source of much controversy, because it could be an indicator of the timeframe and scope of the Federal Funds Rate increase which is expected to take place in 2015. The development of the labour force participation rate as a measure for labour supply is further decisive for the US economy’s growth rate in the medium term. Currently, it is fair to assume that moderate growth will be retained and that this fragile situation implies a continuation of the FED’s hesitant policies.

Secondly: the Japanese government has to accept the failure of their much-vaunted ‘Abenomics’. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had promised to boost inflation and therefore ‘solve’ the country’s problems. The latest economic data, however, suggest a disaster, with all evidence pointing towards the devastating impact of ‘Abenomics’.

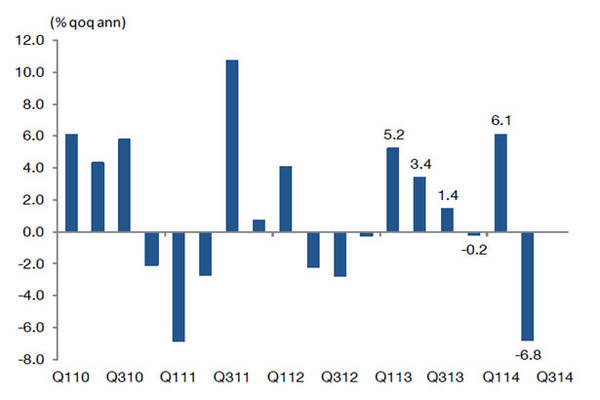

The government itself has retracted its growth prognosis. Contrary to Abe’s claims, according to which the export sector and the entire economy would be stimulated by means of a sharp depreciation of the Yen, the foreign trade deficit is growing because Japanese citizens have to spend more and more on expensive energy imports. There is a significant drop in incoming orders for machinery. Increasing VAT has caused a contraction of the Japanese economy on a par with the drop seen following the catastrophic tsunami that struck the country in March 2011. GDP has dropped by a cumulated average of 6.8% for the year; economists, however, expect a growth rate of 3–5% for the current third quarter. Consumption could be stimulated if (mainly) large enterprises were to pay considerable bonuses to their employees. In addition, as it becomes increasingly difficult for companies to find the workforce they need, opportunities for wage increases become quite likely.

Japan has been stuck in a period of deflation, ergo a downward spiral of prices, for approximately 15 years now. This phenomenon is paralysing the economy because consumers purchase less in expectation that prices will drop further and companies will postpone investments. Attempts to exit this spiral can be judged to have failed and resources for further economic experiments are limited. Japan already has the world’s highest national debt rate which stands at 240% of the Japanese GDP.

Fig. 2: Economic growth in Japan

Thirdly: at a growth rate of 7.4% in the first half of 2014, the Chinese economy, and the governing administration, have definitely set a course for growth, but the threat of a long-term slowdown of capital dynamics was not averted. Separate from China’s own internal societal issues, what is certain is that China is slowly losing its importance as a driving force for global economic growth.

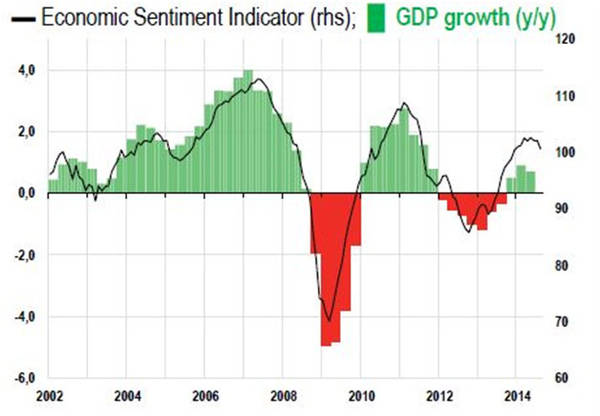

Fourthly: in addition, the data coming out of the EU and the eurozone are equally mediocre. In comparison with the previous quarter, the GDP of the eurozone stagnated in the second quarter after a disappointing growth rate during the first three months of this year. For the EU 28, a slight increase of 0.2% was noted which represents a contraction when compared with the increase of 0.3% seen in the previous quarter. In France, the second-largest country of the eurozone, a zero growth rate indicated a disappointing economic development. In light of the latest economic data, the French government felt compelled to lower its growth prognosis by half, i.e. French GDP will only grow by 0.5%. The prospects for France’s neighbouring country Italy are even bleaker: it is stuck in a recession with a contraction rate of -0.2%. The growth stagnation in the currency union endures and the danger for the region to slide into yet another recession period grows. This would be the third time within six years; after the double dip, we might yet experience a triple dip.

Fig. 3: Economic indicators

Fifthly: in this, the seventh year after the financial crisis, Germany also continues to struggle with the changed economic structures. There is no sign of a strong, sustainable upturn; the German economy has slowed down significantly at the mid-year point. German GDP contracted by 0.2% in comparison to the previous quarter.

At least the core economies were expected to experience a strong upturn which – due to excessive demand – would even lead to a shortage of economic capacity in 2015. Looking back on the past years, the way the economy has developed cannot be explained with well-established economic theories, which are based on a continuous cycle of economic boom and bust. The Federal Reserve has now overestimated the US growth rate for the fifth consecutive year – not just by a little, but by a large margin. However, the FED still clings to its hopes for a sustainable economic upturn and for the US-American economy to return to robust growth rates (see fig. 3).

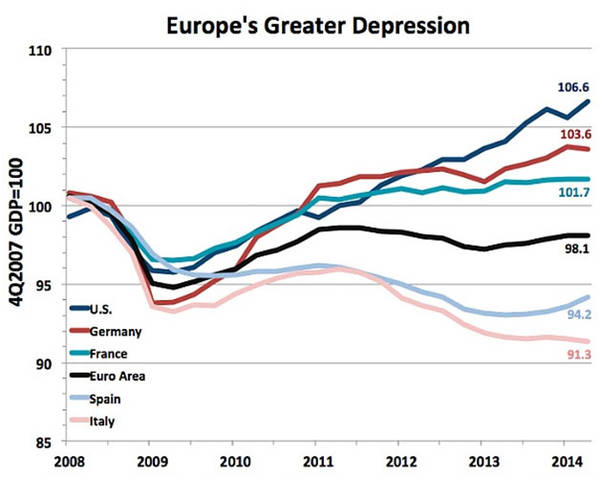

Fig. 4: GDP development in the USA and Europe

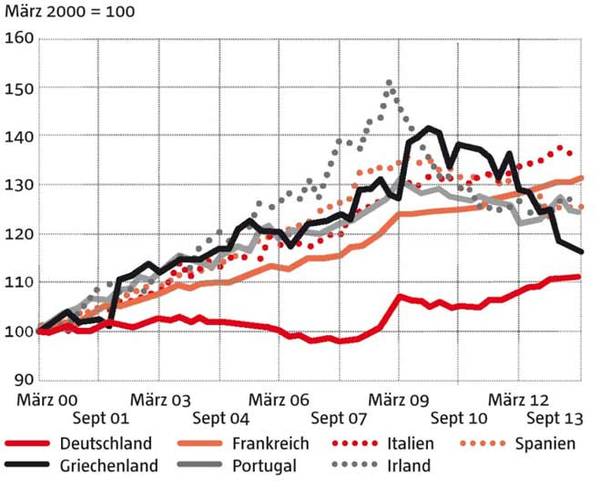

Since 2007, the global economy has been in a continuous state of stagnation. ‘Stagnation’ is often erroneously defined as a longer period of time during which an economy hardly changes. The truth is that during a period of stagnation, we do see some slight changes; the growth rate, however, is below the historical trend and will remain at this low level unless structural changes are implemented. The EU, in particular, has not managed to make any progress in combatting the crisis; overall, economic performance remains below the pre-crisis level. Unemployment rates are depressingly high in the European crisis countries, and the competitiveness of the latter has not improved, despite the widely-applied austerity policies that hoped to achieve this aim. Although most countries have experienced a significant break in the economic trend in terms of the development of unit labour costs – which is the stipulated goal of competition policies – these changes in labour costs are not sufficient enough to strengthen the position of those countries on the international market (fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Development of nominal unit labour costs

In the first quarter of 2014, the government debt ratio increased in the EU as well as in the eurozone. The EU 28 registered an increase from 87.2% to 88.0% of GDP compared to the previous quarter; the currency union recorded a debt increase from 92.7% to 93.9%. Once more, Greece boasted the highest government debt ratio (174.1% of its GDP), followed by Italy (135.6 %), Portugal (132.9%), Cyprus (112.2%) and Belgium (105.1%).

It will still take some time until the foreign debt ratio in the crisis countries returns to what is largely considered to be a ‘normal’ level. At the same time, the investment positions of surplus countries such as Germany and the Netherlands have continuously improved. As such, imbalances keep growing which is why the IMF advocates boosting demand. In Europe, countries such as France and Italy have been demanding a reorientation of policies towards greater growth and flexibility.

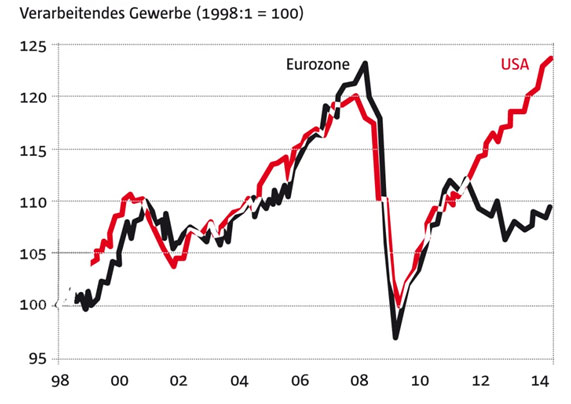

Thus, we may still be some way off actually seeing an economic upturn within the eurozone. In May, companies reduced their production rate by 1.1% compared to the previous month. Portugal saw the strongest slump (-3.6%), while the Netherlands boasted the highest growth (1.1%). In Germany, production was down by an unusually large margin of -1.4%. For the current year, the IMF predicts economic growth of 1.1%. The average industrial production rate of the EU and the eurozone has not yet reached the pre-crisis level. In comparison to US data, the backlog is especially obvious (fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Development of industrial production rates in the eurozone and the USA

Manufacturing sector (1998:1=100)

Eurozone – USA

A boom in Great Britain and malaise in France and Italy

The large gap that has opened up between the big economies is especially worrying. With its strong growth rates, the British economy is outdoing every country in the eurozone. Between April and June it grew by 0.8% compared to the previous quarter. In comparison to the previous year, British GDP even grew by 3.2%, which represents the highest level of growth for more than six years.

Changes in the British economy began to appear when the property sector started to change. Since the Bank of England’s all-time low interest rate did not have the desired effect, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the British minister of finance, put another measure in place: in March 2013 he announced a stimulation programme for the housing market. The state made it possible for buyers to buy houses with a purchase price of up to EUR 750,000, even if their net assets only made up 5% of the purchase price. This means that public funds are used as mortgages and collateral for home buyers. In the months after this programme was announced, house prices changed significantly and the economic growth rate increased. Currently, the country is experiencing a boom in house prices, with property prices in London increasing by 25% over the past year.

This robust growth rate makes up for the British economy’s weaknesses. A much hoped for process of economic reweighting – including areas of international trade – did not come to pass. Instead, soaring house prices have given rise to fears of a new asset price bubble, and British employee incomes are still curbed by sluggish wage growth which does not keep up with the level of inflation.

As a result of decisions taken at a political level, the British economic cycle is subject to the very same forces which led the country into its current crisis: debt-financed consumption and a property boom; the provision of subsidies for mortgages instead of attempts to tackle structural weaknesses and imbalances. The country remains dependent on the financial sector; industry still contributes a meagre 11% to British economic output. The current account balance is chronically negative; imbalances between the regions have intensified. Although 1.4 m jobs have been created in the corporate sector, they are mainly in the service sector. The budget consolidation process is barely progressing. And if the impending referendum on Scotland’s independence goes the way of the ‘yes’ camp, the British economy will be put under even more strain.

While Great Britain is experiencing an economic boom, despite not having taken any steps to tackle its underlying problems, France and Italy continue to lose ground. Both EU member states seem to be making little progress with regard to the implementation of reforms they claimed would boost productivity and employment. Elsewhere growth prognoses for Spain were raised to 1.5% whilst Italy is only expected to grow by 0%.

Given the size of the Italian economy and the scale of its public debt, which amounts to 133% of GDP, the lack of economic growth remains the greatest individual threat to the stability of the currency union. Matteo Renzi, the Italian prime minister, has been using his political capital to enforce changes to fiscal rules which would make it possible for Italy to borrow more money for higher investments. Italy’s difficulties in trying to regain its pre-crisis level have been particularly pronounced.

When Renzi became prime minister in February 2014, he announced an ambitious 100-day programme to revive the country’s economy. Since then he has achieved very little, and has extended this term to 1,000 days. The only substantial reform Italy may expect this year will concern the electoral system and the senate; whilst such a reform undoubtedly has great symbolic worth for the Italian political class, it is of little importance to the country’s economy. Extensive reforms of public administration, the legal system, public expenses and the labour market have been announced, but little is known about the details and a clear time frame has yet to be defined.

Alongside Italy, the other country in the throes of economic woe is France. Here, the private business sector contracted in June for the second consecutive month. The manufacturing industries, as well as the service sector, are struggling, with the number of orders falling. The purchasing manager index (which measures the mood amongst managers of large companies using surveys) for the French industry stands at 47.8 (down from 49.6 in May); the same indicator for the service industry currently lies at 48.2 (down from 49.1).

Therefore, unemployment is steadily spreading and no stabilisation is in sight. Cautious estimates predict the curve to flatten at the end of 2014 at the earliest; a real reduction can only be expected at the end of 2015. In April 2014 the number of registered fully unemployed people in France had increased by 0.4%, which corresponds to an increase of 14,800 individuals. The situation in March, when only 1,600 newly unemployed people were registered, has proven to be misleading. Not even the government, which, after two years in office, is facing an almost insurmountable chaos of issues, was surprised by this development. After President Hollande’s first year in power, an economic upturn and a change for the better seemed a potential prospect. Since then, the number of fully unemployed people has increased by 130,000.

France is on the dangerous road to becoming accustomed to mass unemployment. By the end of April 4.986 m people had registered as job seekers at the continent’s job centres, where records on both fully and partially unemployed persons are kept. With a total population of 66 m, including French overseas territories, the overall number of unemployed amounts to 5.286 m. It is obvious that a majority has also indirectly been affected by the labour market crisis – through their families, a reduced number of entry-level job offers, difficulties when changing jobs, fear of job loss etc.

These are also the reasons behind widespread social unrest. With a youth unemployment rate of 24% and a large number of unsolved issues in the education system, many people are extremely pessimistic about the future. Current economic data increasingly confirm the suggestion that France is not on the path towards turning its economy around.

Unemployment in the eurozone has decreased to 11.6%. Thus, in the 18 countries of the eurozone, approximately 18.5 m women and men were unemployed in May. The unemployment rates of the euro countries are substantially different. Whereas Austria boasts a rate of 4.7%, in Spain it lies at 25.1%. The situation regarding youth unemployment has improved slightly: standing at 23.4% in April, it decreased to 23.3% in May.

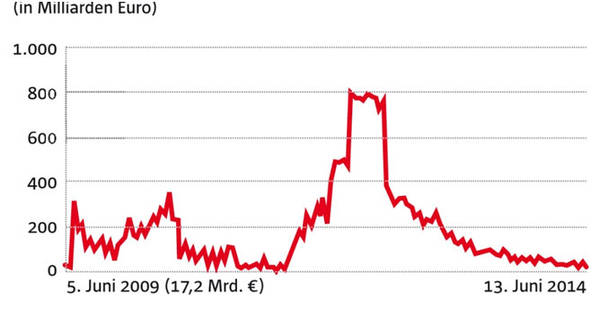

The ECB as an economic policy maker

The austerity policies applied by the economic elites make the European Central Bank (ECB) Europe’s last resort. The announcement two years ago that, if necessary, the ECB would buy government bonds from those countries hit by the crisis, has led to the ECB now having more room for manoeuvre. On the one hand, the bank balances at the ECB have shrunk over the past years to as little as EUR 17 bn, which is the figure given today (fig. 7). On the other, more and more doubts are being raised about the proposition that greedy banks are solely to be blamed for declining volumes of credit. Moreover, it is increasingly the case that people and companies are eschewing loans in favour of paying off their debt. Due to escalating unemployment and centrally managed austerity measures, purchasing power is decreasing in many countries. Why should an Italian, Spanish or Portuguese company or member of the middle class take out a loan in order to expand his or her business if there are no prospects for business expansion? In fact, reports from Spain and Italy are indicating that today the majority of loans are not taken out to fund investments, but to provide for the company’s survival.

Fig. 7: ECB deposits

(in bn euro)

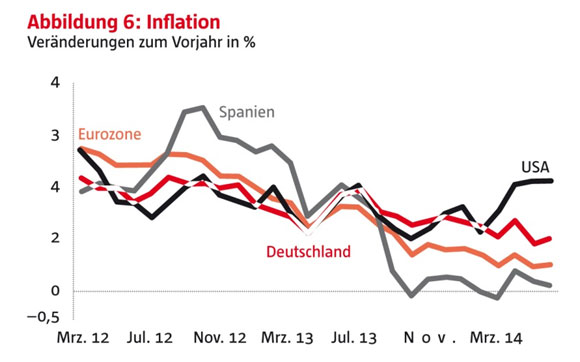

In June, ECB boss Mario Draghi introduced a de facto economic growth package by lowering interest rates. This included, amongst others, a negative deposit rate and specific long-term loans to banks. By doing so, he aims to tackle high unemployment rates in the eurozone which are the result of the stagnation period the continent has endured over the past years. The ECB is currently witnessing a period of extremely low inflation, but sees no risk of an increased deflationary pressure within the eurozone (fig. 8). “According to our prognoses, we are currently not anticipating any increased or spontaneous deflation risk such as people changing their consumption habits or postponing any purchases because they believe that prices will continue to decrease,” says Yves Mersch, member of the ECB’s Executive Board. “What we are witnessing right now is a longer period of very low inflation. And such low inflation means facing the increased risk of having no buffers left should the European economy be hit once more by an unpredicted external shock.”

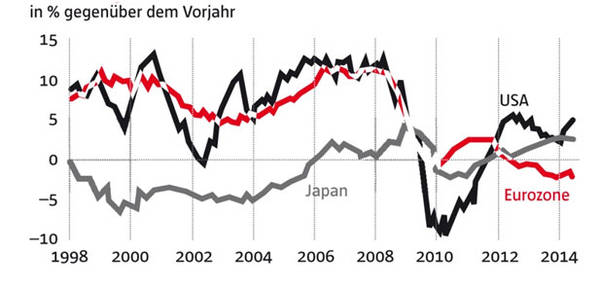

Fig. 8: Inflation

Changes compared with the previous year in %

Generally speaking, the single currency used by 18 of the EU’s member states has recently been under pressure and lost ground in comparison with almost any other relevant currency. The ECB has opened the floodgates for the continued easing of monetary policies, not only by enabling negative interest rates and introducing targeted liquidity measures to improve loan conditions for small and medium-sized enterprises, but also by taking preparatory measures for further unconventional actions.

It is to be expected that the ECB will stay quiet while fears of a debt crisis remain restrained and the organisation awaits the results of a stress test for banks (to be announced at the end of October). Instead of building confidence, this test could cause further distrust. Further expansive steps would be necessary should price increases continue to be in decline. A lowering of expectations with regard to inflation can be taken as evidence of sluggish growth in the eurozone and further increase the pressure the euro is facing. Reaching a new annual low would open the doors to greater depreciation of the euro within the present slow currency fluctuation process.

For this reason, the ECB has recently lowered the base rate further and established a negative deposit rate of interest. According to Yves Mersch, interest rates should remain low for a long period of time – possibly until the end of 2016 – as long as the inflation rate stays significantly below the target rate of 2% which the ECB defined as an indicator for price stability. ECB measures ensure that banks are generously provided with loans, but the credit institutions do not pass these funds on to companies. Moreover, companies are hesitant to provide inexpensive loans for investments which fund the expansion of social production. Thus, the key problem is insufficient demand and not the high debt level and high interest rates for external financing.

Six years after the onset of the crisis, the volume of credits granted to American and European banks remains significantly below pre-crisis levels (fig. 9). In June, the volume of credits provided by US banks increased by 4.8% compared to the same period last year. Prior to 2008, we witnessed a yearly mean growth of 10%. The volume of credit has also increased by 2.5% in Japan. However, even before the financial crisis the growth rates in Japan were significantly lower than those in the USA or Europe.

Fig. 9: Credit Growth

in % compared to the previous year

The eurozone remains the only region which has not yet mastered this change in trend: in the past month, banks have granted a further 2% fewer loans than in the past year. In 2008, credit growth did not collapse as it did in the USA. However, across the pond the volume of credit started to grow again in mid-2011, whereas in Europe we are experiencing the very opposite. Apart from insufficient demand within society, the hesitant reaction Europeans have had towards the banking crisis is to blame for this phenomenon. While financial institutions in the US were forced to put their balances in order relatively quickly, European banks still find themselves right in the middle of this process. Corporate bank lending also suffers from this reality.

A strategic option for the new European Commission

The EU top-level staff restructuring process is nearly complete. What actions and policy fields are to be expected in the coming months?

1. ECB president Mario Draghi is alarmed by the all-time low interest rates on government bonds within the EU, the insufficient credit supply (especially for SMEs), and the continued decline of price inflation to 0.3%. Even Draghi has finally taken notice of the fact that the sustained application of austerity policies has slowed down the fragile growth process of the European economy to an alarming extent. Draghi emphasises that he does not advocate a deviation from applied consolidation and structural policies, but that we cannot continue as we have been doing before. Thus, we will experience the further development of expansive monetary policies.

2. The contradiction between consolidation and growth promotion has shaped political rhetoric over the past months. Currently, it is Italy’s turn to take over the EU Council Presidency. Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi is making fresh attempts to revive a growth initiative. On 6 October, he will invite the Heads of State and Government of the EU member states to a special meeting on economic development within the EU. The French president, Francois Hollande, has also called for greater commitment to growth in Europe. The recent government crisis in France has increased the pressure on him to finally deliver results. Hollande has complained about the high exchange rate of the euro and the low inflation rate within the currency union. The growth-enhancing reforms that have already been put in place “will not be able to take effect until the rest of Europe has been mobilised,” said Hollande.

3. In addition to the ECB’s enforcement of expansive monetary policies, the EU Commission will launch investment programmes in order to develop public infrastructure. The future EU Commission wants to initiate a EUR 300 bn investment programme for the next three years that includes an increase in the European Investment Bank’s (EIB) capital which is owned by the EU member states. This has apparently already been agreed upon by governments and national central banks. The money shall be used mainly for infrastructure, such as the expansion of broadband internet and energy networks, but also for education, research and promoting energy efficiency. The Commission will also probably try and boost the dynamics of its youth unemployment programmes.

These approaches do not represent a policy change. The combination of austerity and neoliberal structural policy with few growth stimuli will not end the stagnation period the European economy finds itself in. This phase can only be addressed through public loans and adequate investments. It makes sense to facilitate this via the European Investment Bank, but EUR 300 bn, as budgeted by Juncker, is clearly not enough. Incurring even higher debts with the aim of boosting or securing long-term growth is particularly reasonable in an environment with low real interest rates. Similar arguments can be put forward regarding expenses for the improvement of ecological structures, as well as the education and health sector. The European trade unions have long been demanding a programme for the reorganisation of economic structures in the medium-term.

A geopolitical turning point

As a whole, the countries hit worst by the crisis are showing small signs of recovery; economies are contracting to a lesser extent (or not at all), and labour markets have also stabilised at a low level. The medium-term expectations for the global economy remain restrained. At 7.4%, economic growth in China in the second quarter has proven to be more robust than expected, compared to the previous year. Furthermore, monetary policies designed to stabilise the economy remain abundant. However, apart from the unresolved structural problems addressed above, additional uncertainties originating from international conflicts pose a threat to the economy.

Currently, the greatest threat to the dynamics of the European economic system is foreign trade. The downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 in Eastern Ukraine, killing all 298 passengers on board, has put more strain on an already tense situation, with war being waged between the Ukrainian government and pro-Russian separatists in the region of Donetsk.

By applying sanctions, the EU member states are currently fostering massive contradictions and conflicts on the Russian markets. Russia’s economic situation is notably dire and not restricted to its automotive market. The Russian middle class continues to save out of fear that inflation will rise – even today the inflation rate stands at more than 7%. This attitude is also reflected in an increased withdrawal of capital: in the first quarter of 2014 alone, enterprises and banks withdrew USD 70 bn from the country.

EU sanctions against Russia, however, also affect Western economies, and that includes German exporters. “This year we are expecting a slump of 10% in Russian exports,” says Volker Treier, head of foreign trade at the Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce (DIHK). “Thus, we stand to lose EUR 4 bn. This is a loss that will impact us significantly: around 300,000 jobs in Germany are connected to business relations with Russia.” The sanctions against Russia will result in considerable losses for German exporters: in the first two quarters of 2014 they earned almost EUR 3 bn less than in the same period of the previous year.

The Russian growth rate has been under pressure for quite some time. In 2011, the third biggest emerging market still grew by 4.3%, whereas it only grew by 1.3% in 2013. By the turn of the century, increasing oil costs and high commodity prices triggered a consumption boom which caused more and more production facilities (which had remained unused after the fall of the Iron Curtain) to be used to full capacity. Investments in capacity development and modernisation, however, were low. For 2014, experts are expecting Russian GDP to grow by 0-1%. Partially due to a weak rouble, the inflation rate now stands at 7.5%. Unemployment is low, but so is real wage growth and retail sales are at their lowest in years. Even fixed asset investments are declining, and credit costs are high. Russia is suffering a profound structural crisis. In addition to the direct consequences of the Ukraine conflict, the insecurity fuelled by international sanctions further hampers the country’s ability to overcome this crisis.

The Ukraine finds itself in a similar situation; the country’s economy notched up hardly any positive growth rates in 2012 and 2013. Now, with battles raging in the country’s east and the secession of the Crimean Peninsula to Russia, even government sources expect a drop in GDP of up to 6.5% in 2014, and an inflation rate increase of up to 19%. At the end of August, the country received a second aid payment from the International Monetary Fund, which means the country has now received a total sum of USD 4.6 bn from the IMF. Since the beginning of this year, the national currency, the hryvnia, has depreciated by more than 60% compared to the US dollar. Exports to Russia, an important trading partner for Ukraine, have experienced a slump, falling by 24% between January and May. Production in the industrial centres of Donetsk and Luhansk, two now fiercely embattled areas, used to account for 16% of GDP. As long as this volatile situation persists and the government is unable to find the time or the will to enact basic reforms – in terms of corruption and bureaucracy, Ukraine is said to be even ‘worse’ than Russia – the country will not experience a sustainable economic turnaround.

Russia is one of Germany’s most important trading partners and one of its key investment centres in Eastern Europe. In comparison to other economic regions, Russia may not be of central relevance, but this escalating economic war has destructive consequences for the global economy.

The EU also has to deal with massive instability around its southern borders, e.g. in Syria, Israel and Palestine, Egypt and Libya. Political unrest in Turkey has also acted as an obstacle to investment. The picture looks different in the long term: armed conflicts in the eastern and southern Mediterranean regions have caused an increased movement of refugees. The challenge of dealing with large numbers of immigrants has become a delicate political issue, particularly in Greece and Italy. With the Schengen agreement, those countries at the European periphery in effect became responsible for policing the EU’s border. Once having entered the countries of the periphery, immigrants tend to quickly head for the rich north.

At the same time, this influx of migrants has become the main target for right-wing, eurosceptic and xenophobic political parties. The EU does not implement the same policy along all of its borders, thus mainly the weakest elements suffer from the increased burden of duty.

Instabilities originating at the periphery of the EU are passed on to the community, e.g. the conflicts in the Middle East can be a burden to countries such as France, Great Britain or Germany because they cause uproar within each country’s respective Muslim community. Likewise, Eastern European governments with large Russian minorities worry about the destabilising effects of the war in Ukraine.

Association agreements offered by the EU to its neighbouring countries – e.g. Turkey, Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, Moldavia and Serbia – did have a stabilising effect for certain period. The consequences of the crisis, however, have also manifested themselves in these countries and led to economic and social regression and the political consequences that that entails, as the Ukrainian example shows drastically. Thus, the limits to this strategy have been reached.

For the first time since the break-up of Yugoslavia, an aggravation of the confrontation between the NATO and the Russian zones of influence carries with it the risk of an armed conflict in Europe.

These cumulative geopolitical risks pose a threat to European cohesion and its financial stability that is as serious as the euro crisis. And as is the case with the latter, the solution lies in a continuous integration of the EU, which, however, is also in need of a radical shake up. However, just because it is desperately needed does not make it any easier to achieve.

Geopolitical risks remain the permanent companion of the economic cycle. A dramatic aggravation of the situation in the energy sector is not to be expected given that the global community tries to consistently avoid friction in global cooperation. Apart from that, economic stabilisation in the USA and emerging markets, as well as a pro-business approach in the eurozone’s financial and monetary policy, are providing a relatively stable overall configuration that should last until the end of the year.

Nonetheless, we have to accept that the current period of stagnation will persist as a result of policy-makers’ reluctance to push through any structural interventions. Instead of holding firm to austerity policies and hoping for an accelerated accumulation of capital, expansive public investment policies should be introduced, accompanied by alterations to the usual distribution of wealth and power (with the goal of strengthening the EU economy), debt restructuring and a contraction of the financial sector. Otherwise, a lost decade will ultimately be our fate.

Joachim Bischoff is coeditor of Sozialismus. In September, the publishing house VSA: Verlag Hamburg will release his introductory pamphlet ‘finanzgetriebener kapitalismus. entstehung – krise – entwicklungstendenzen.’ (‘Capitalism Driven by Finance. Origin – Crisis – Tendencies of Development.’)