The Italian economist and political scientist Riccardo Petrella on the current crisis.

Mr. Petrella, in this stage of the pandemic medical personnel are constantly referred to as if they are soldiers: "at the front lines of fight with the disease". There is also constant talk of the need for the production of testing kits, respirators, protection suits, and vaccines in the sense that we need to be armed against the enemy. What does this mixture of militarisation and medicine mean for our future? Does it help the fight against the disease?

The use of the concept of war to define the state we are in because of the Covid-19 pandemic is not only inappropriate, but mystifying and dangerous. This military metaphor of fighting against the coronavirus has created a rather unhealthy atmosphere, making us imagine that at the origin of the disgrace there is an enemy, an external culprit. Hence, in the beginning, claims of plots, laboratory errors, and provocateurs.

More realistically, we can say that militarization would serve as a cover, justification, or alibi, with the aim of minimizing or even denying the potential responsibility our society holds in the emergence and murderous spread of this pandemic; to make people accept as inevitable the very heavy, negative consequences that the pandemic is causing and will cause in terms of unemployment, loss of income, impoverishment, conflicts, social inequalities, devastation of lifestyles. The costs of which will be paid by the most vulnerable, the most impoverished, the excluded, the uncompetitive.

In the end, the militarization of the fight against the pandemic is above all a reiteration, applied to a disease, of the concept that the world is a theatre for a permanent economic war for survival. This is the reason, in my opinion, why the business and financial oligarchies insist on an immediate return to work and on the uninterrupted continuation of economic activities that are said to be strategically important for the competitive economic survival of a country.

What does the pandemic and state of emergency which we have entered mean for the EU economy? What reforms will this crisis accelerate?

An initial answer was just given by the agreement reached on the evening of 9 April between the EU’s eurozone members (the Eurogroup) on a joint response to the pandemic. This much-awaited decision is a poor example of solidarity between the leaders of the EU.

Admittedly, it includes an increase in the amount of financial resources available, in particular from the capital markets, aimed at

a) mitigating the devastating effects on workers’ employment and income (the so-called SURE package giving access to 100 billion euros in loans),

[SURE, Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency, is a temporary loan-based instrument for financial assistance for EU Member States to protect employment in the Covid-19 crisis]

b) supporting companies going out of business and losing revenue through the creation of an EIB (European Investment Bank) fund of up to 200 billion euros, and

c) granting state aid of up to 240 billion euros under the European Stability Mechanism (the famous ESM, which has been severely criticised for years by progressive European forces).

There are also the traditional European funds (agricultural, regional, and so on) which states have been granted greater flexibility in the use of… There is also the temporary and provisional abandonment of constraints imposed by the Stability Pact, which several member states considered stupid and anti-European.

In any case, these decisions do not solve any long-term structural problems in the EU’s economic and financial architecture, which has been at the heart of the political debate in recent years on the future of the EU and the political and social credibility of its integration as a "European community".

It can be said, without forcing the truth, that the agreement of 9 April was not the opportunity hoped for by many European citizens to initiate structural changes necessary to revitalise the European project. The same is true on a more general level: European leaders missed an opportunity to redesign the role of the state and the public in relation to the current predominance of privatisation and monetising of life and public services; to change the criteria for setting investment priorities (what about military spending, will it continue to dominate national choices and global relations? What about harmful spending devastating the ecology of soils, forests, waters, oceans, etc.? Will financial returns continue to prevail over the rights and health of human beings and other living species on Earth?).

Leaving the strongest states free to decide the use of their financial resources and increasing struggling states’ access to credits (debt/prison), even in the case of EU-guaranteed Eurobonds, according to the principles and rules in force, is a minor good thing in the interest of business and finance for the maintenance of an inadequate and unjust system, and a great contribution to the ongoing destruction of European integration.

The world has entered an economic crisis, which they say, in the best case will be as bad as the one in 2007-2008. There is also a strengthening of security controls over the population. What will the pandemic, the state of emergency, and the economic crisis mean for human rights, democracy, and "the utopian projects" of global civic society, which are dear to your heart?

Looking back to the agreement of 9 April, I am afraid that my fears about a world that will be even more fragmented, unequal and unjust after the pandemic are rather justified.

Indeed, under the influence of the opinions expressed by the ruling classes and supported by the vast majority of the media (all categories), citizens – the so-called "people on the street" – do not seem to be pushed, in reaction to the current dramatic situations, to think and act globally, towards a perspective of equality and universality of human rights and the rights of nature. The majority are, above all, concerned about their future, their security, their survival. This is not without reason, considering the economic and financial responses given to the coronavirus in Europe, the United States, Brazil, India…. People seem to be led to fall back on nationalist, and even xenophobic, racist positions and behaviours.

Because of its inadequacies and weaknesses (no financial alchemical combinations can conceal them), it is highly likely that the April 9 agreement will be easily exploited to exacerbate Italian animosity towards the Germans and the Dutch and vice versa. As is the case, within Italy for example, of contempt and racism held by some Northerners towards the people of the Southern regions.

And what can we say about the fate of the 2.1 billion people who do not have access to drinking water and the 4.2 billion who do not know what a health service is? What, at the moment, are radical measures being taken to stop the factors which cause the deaths of 7.9 million children under the age of five every year due to diseases caused, amongst other things, by a lack of drinking water? Where are the decisions taken at the global level to stop the theft of life from the 1.7 billion homeless and the 2.1 billion adults without proper work, who are exploited and unprotected? Where are the decisions to stop, after the pandemic, military spending and the sale to private capital of the rights to life and artificial intelligence?

There will have to be strong signs of a reversal of trends to think that the world after the pandemic will be different from the world before. Admittedly, a little more public money will be spent on healthcare, the environment, quality of life and security in the face of the major risks associated with the effects of the ongoing climate disaster. But this, if things remain the same as they are likely to, will only benefit the wealthy social strata, the financially insulated.

Some people say China will be the winner of this crisis, because it has already resolved its coronavirus problems and is now engaging in active diplomacy to support European countries. What will the system of international relations look like at the end of this crisis?

Your question on China and the future of international relations on a global scale underscores the fact that the world’s leaders are still guided by the logic of the present and a future world shaped by the struggle for economic and military power between peoples and states. Other scenarios are considered unrealistic, utopian, and far-fetched.

The available demographic data is reliable. It shows an accentuation of the tendency to make Earth overwhelmingly a home to communities and countries which, not long ago, were considered weak economic and political powers. On the other hand, forecasts on the world’s economic and technological power in 2050 are more fragile and sketchy. They do not allow us to make strong statements. They cast a rather weak light, but enough to give a vague idea of what is likely to become the "state of things" in 2050.

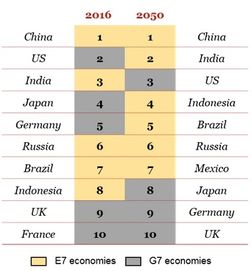

Emerging markets will dominate the world’s top 10 economies in 2050 (GDP at PPPs)

Note: gross domestic product (GDP) at purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusts for price level differences across countries, providing a better measure of the volume of goods and services produced

Source: IMF for 2016 estimates, PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited (PwC) analysis for projections to 2050, online at the PwC website

On the subject of economic trends (The World Economy in 2050, see above) it can be said that the direction is towards a relatively significant reduction in the "gross" weight of the so-called "developed" economies in the world economy. Of the top ten countries in terms of GDP in 2050, four will belong to the Western world (the USA, Japan, Germany and the United Kingdom) and in terms of population, only one (the USA). This means (and this is even more true if we take the top 30 countries in terms of GDP) that developed countries would maintain their relative supremacy in terms of per capita economic (especially financial) power. As far as the countries which are called "emerging" (by the dominant players) are concerned, it is interesting to note that for the time being, the scenarios also favour the continuation of current trends. Not surprisingly, the top ten include China, India (1st and 2nd), Indonesia (4th), Brazil (5th), Russia (6th) and Mexico (7th). This does not mean that the affluence of their populations will increase. It is perhaps conceivable that 400 million Indians will manage to become affluent out of a population of 1.6 billion people. Perhaps in China there will be 500 million out of 1.4 billion. Moreover, it is difficult to imagine, as things stand at present, that countries such as Brazil, Indonesia, Russia and Mexico, which are characterized by enormous internal social, economic and political inequalities, will succeed in turning the situation around in 30 years. This could only happen if a class of Lula-style leaders multiplied and remained firmly in power for one or two generations.

As far as technological power is concerned, I have taken the number of patents applied for (and obtained) in the field of living organisms (molecules, cells, genes…) in the plant, animal and human world and in the field of algorithms (artificial intelligence) as a significant indicator of countries’ potential techno-scientific capacities. According to the latest WIPO report (World Intellectual Property Organisation, Report 2019, The Geography of Innovation: Local Hotspots, Global Networks) the USA, Japan, and the countries of the European Union (in particular Germany, the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands and Scandinavian countries) account for 70% of the patents filed in the "families" of patents that are strategically more sensitive and decisive. Only five countries in the rest of the world (China, India, Israel, Singapore and South Korea) have managed to occupy a rising position, thanks also to the fact that Western countries and Japan, for reasons of competitiveness and convenience, also tend to file part of their patents in the latter countries. In other words, only the repeal of legislation on private and for-profit patents (introduced and imposed by the United States in 1980 and then by the European Union in 1998) could stop the technological superiority of Western countries. The objective would be to remove market logic and the interests of global financial capital from technological and scientific knowledge. Knowledge must become a global public good for the service of all on Earth (all living species included). If this does not happen, I am not prepared to bet even one euro on a future of affluence as a collective solution to the current and future disasters.

Riccardo Petrella is an Italian economist who was a scientific and technology policy analyst to the European Commission between 1979 and 1995, becoming a witness and voice of dissent over the EC’s definition of Europe as a union of competition. He is the main force behind the report "Limits to Competition" by the Group of Lisbon that has criticised the neoliberal reforms undertaken by the Commission of Jacque Delors, that serve capital and markets, but undermine the achievements of Post-War Europe. Petrella worked between 1967 and 1975 as a scientific secretary, and then as the director of The European Coordination Center for Research and Documentation in Social Sciences in Vienna – an organisation that brought about scientific exchanges between East and West Europe during the times it was divided. The Italian university professor taught between 1982 and 2005 at the Catholic University of Leuven (Belgium); including courses such as "Scientific and technological politics" and "Economic globalisation", and has been a lecturer in other universities and countries, too. Between 2005 and 2006, he was president of the Water Company of Puglia (Italy). In 1997, he founded the International Committee on the World Water Contract, which has the former Portuguese president Mario Soares as a president. In 1998, Petrella published "The Water Manifesto", where he unveiled his vision for water as a "common good".

Interview conducted by Vladimir Mitev, editor-in-chief of BARICADA Romania

Originally published at the website of The Barricade (13.04.2020)

titled "Riccardo Petrella: The militarization of pandemic is dangerous"