The transformation of the Czech Republic, specifically of Czechoslovakia from 1990 to 1992, is a topic that relates not only to economics, but also has legal, social and political aspects. It is subject to many interpretations and also poses a fundamental question: whether the process is complete.

This question is also accompanied by other important issues: what manner of transformation the Czech Republic went through, whether this transformation can be considered successful, and how the Czech Republic has integrated into the global economy, or the European economy. These issues are only the most central topics that we will consider in the text to follow.

With respect to the topic in question, it is not possible to avoid the methodological approach of political economy. Description of individual stages cannot be sufficient, because it would take into account neither the interests of domestic actors, nor foreign actors. The countries of Central and Eastern Europe underwent their transformations in a specific international context, both political and economic, which also had a very important ideological aspect.

The Anglo-Saxon approach distinguishes “transition”, which indicates a final state (the completion of transition), and transformation (used in this context) to express the various initial statuses of various countries, the diversity of approaches and the like. With respect to the final state, we can see the following similar features:[1]

- the implementation of a market economy (however, it would be possible to apply a wide range of approaches; see also the Theoretical Approaches section)

- the dominance of private ownership that anticipated specific privatization procedures (and again there are many of them)

- integration into a system; i.e. the system of capitalistic economy. It is obvious that the “fall” of one political and economic system strengthened (in some interpretations, directly saved) the capitalistic economy. However, it is necessary to more deeply understand what stage this capitalistic economy was at (see below), as well as other key questions: how the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, specifically the Czech Republic, integrated into this global economy, and what consequences the Czech Republic has faced so far.

There are many other factors that determined the form of the transformation process. Geographical position, inherited economic structure, the ability of the state to control the transformation process within the framework of an institutional approach, the above-mentioned international aspects (above all the role of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank) and others.

State Socialism and Central Planning

With respect to any transformation process, it is necessary to compare the initial state, desired final state and the procedures (in the case of comparisons) that will lead the economy as well as the overall society to this goal.

What was the initial state?

The denomination of “system” itself arouses lively controversies. Specifically in the media, terms as totalita (totality) or communist regime are used, but not in scholarly literature. The term state socialism has been used most often, as well as real socialism since the 70s. The term state socialism also indicates the interconnection between the economic and political spheres, which cannot be separated.[2]

It is necessary to clearly distinguish the various periods state socialism[3] (and its economic component of central planning) underwent, each with its own problems and economic results. Within the Eastern Block, Czechoslovakia had a status of a developed country, which was also reflected in the structure of its foreign trade and the GDP per capita in comparison with the West.

In general and in brief, it should be mentioned that the mobilization strength of central planning strongly manifested itself during the post-World-War-II reconstruction era. There were even fears that this system would prove more effective than the Western one (at that time, the West was seeing the development of the social state). The turning point for both systems occurred during the 70s. The West responded with a paradigm shift from Keynesian economics and the social state to a neoliberal understanding of economics. At the political level at that time, the changes were made by British Prime Minister M. Thatcher and US President R. Reagan. The Eastern Bloc failed in its attempt to implement the system of central planning towards better quality, meeting technological demands and specifically consumer goods. Thus, starting from the ’70s, it has faced stagnation (similarly to the West), but contrary to the West, it has not created any mechanisms to "postpone" the problem. We can divide the individual stages as follows:

- the implementation of central planning, the considerable mobilization of resources for post-World War II reconstruction, structural changes (industrialization in many countries), large-scale investment, the development of principal sectors with a focus on heavy industry, extensive growth and a high growth rate.

- The attempt on the part of the elite (see the Prague Spring, for example) to intensify and develop innovation activities together with the application of partial market principles. This attempt failed, thanks to external contribution.

- Stagnation stage (approximately since the 70s), the micro-sphere learnt how to use central planning to meet its needs, the conservation of structure, the fear of change.

The following tables outline the situation, showing economic growth and GDP per capita for the Visegrad Group and the Soviet Union.

Table No. 1: Economic growth

|

Countries |

1950–1973 |

1973–1989 |

1973–1990 |

|

Czechoslovakia |

3.09% |

1.38% |

1.12% |

|

Hungary |

3.6% |

1.32% |

0.85% |

|

Poland |

3.45% |

0.39% |

-0.25% |

|

the Soviet Union |

3.35% |

0.99% |

0.75% |

|

Western countries |

4.05% |

2.07% |

1.99% |

Source: Myant, M., Drahokoupil, J.: Transition Economies, p.12

These significant statistics confirm and specify the above-mentioned information. Though Czechoslovakia shows the lowest economic growth among all the compared countries, or the countries at the post-War-II stage of development, later it was able to sustain greater growth compared to the other Eastern Bloc countries up to the beginning of the 90s. We can also see how the slump (transformation depression) in 1990 was influenced by the data from 1973. It is obvious that the 70s saw an economic slowdown in both systems, but it was sharpest in the Soviet Union. Surely, some role was played by the so-called crude oil anti-shock in 1986, because the export of primary commodities, specifically crude oil, was already the Soviet’s Union driving force at the time.

Based on Table No. 2, we can deduce that Czechoslovakia overtook the selected Eastern Bloc countries in the 50s, and maintained this leading position through 1990. Nevertheless, the level of GDP per capita in all the countries decreased in comparison with the West: i.e. they diverged from the Western level.

Table No. 2: GDP per capita, % of Western level.

|

Countries |

1950 |

1990 |

|

Czechoslovakia |

76.5% |

53.3% |

|

Hungary |

54.2% |

40.5% |

|

Poland |

53.4% |

32.0% |

|

the Soviet Union |

62.1% |

43.1% |

Source: Myant, M., Drahokoupil, J.: Transition Economies, p.13

If we now summarise the basic features of central planning, we will better understand the tasks set by the transformation process. Contrary to a chaotic market, planning should have provided several advantages – primarily the overall balance of supply and demand, without the overproduction (or underconsumption) typical of capitalism, and therefore without any economic cycle. The other basic features include prevailing state ownership[4], central planning and coordination with the help of quantity indicators[5].

From a structural perspective, central planning – partially due to the tendency to use, or the ease of using quantitative indicators – favoured heavy industry, and economic success was measured in terms of volume (tons of steel, coal …). The service sector was underestimated. With respect to the Soviet Union, it is necessary to mention a large proportion of resources for military and space research, to the detriment of civil production of course. However, the range of possibilities for involving private sector varied across the Eastern Bloc countries (it was higher in Poland and minimal in Czechoslovakia, for example).

Centrally planned economies had a high level of social insurance: starting from education and health care that were free of charge, up to subsidised food, accommodation, pensions, etc. Czechoslovakia in particular had a very low level of inequality.

As mentioned previously, state socialism cannot be understood as a uniform period. Poland and Hungary tried several different reforms. In Hungary for example, the liberalisation of prices was already under way before 1989, as well as authorization of foreign direct investment and other reforms. The economic situation in Poland was very difficult, and thus before the regime collapsed, there were discussions with the opposition. Czechoslovakia was a country that refused Gorbachov’s reforms. The Prague Spring was followed by the so-called “normalization” period, which was typified by stagnation in the economic sphere and resistance to changes or reforms at the political level. Therefore, the "fall of the regime" only occurred after neighbouring countries, and when initial economic and political conditions were more stabilised.

Table No. 3: Export to key markets (%) 1989

|

Country/Key market |

the Soviet Union |

Other socialist countries |

European Community + EFTA |

|

Czechoslovakia |

32.9% |

23.1% |

23.5% |

|

Poland |

20.8% |

14.0% |

43.6% |

|

Hungary |

25.1% |

15.9% |

35.6% |

Source: Myant, M., Drahokoupil, J.: Transition Economies, p. 43

Table No.3 shows that Czechoslovakia’s trade with the West was the smallest among the countries of the Visegrad Group in 1989, while it was the most interconnected with the Soviet Union. Of course, this resulted in a sharp shock after the unexpectedly rapid disintegration of COMECON and the necessary reorientation towards Western markets.

The Theoretical Concept of the Transformation Process: the Washington Consensus vs. the Institutional Economy

The discrepancy between the then-dominant Washington consensus (which has discredited itself to a large extent) and the so-called institutional approach is sometimes replaced by a difference in the speed with which measures are implemented. On one hand, there is so-called shock therapy – expressed, for example, by J. Sachs’s slogan “leap into the market economy” – and the gradualist, stepwise approach. Before we analyse the Washington Consensus and the institutional approach, allow us to explain this distinction in more detail.

The shock therapy approach is based on the interconnection of political and economic factors. With respect to its political aspect, there were concerns about a possible reverse of this process. In the case of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic, there were efforts to create the "elite" quickly, an elite that would support the transformation process, or its specific form under the leadership of V. Klaus, because this elite would be involved economically. With respect to the economic sphere and shock therapy, there was a conviction that the market mechanism itself would be easy and fast to implement, and it would result in a change of the key actors’ behaviour similarly quickly. The famous recipient of the Nobel Prize in economics J. Stiglitz later called this approach market fundamentalism and primitive textbook economics that has little in common with reality.

In its substance, the gradualist approach did not necessarily differ fundamentally from the Washington Consensus. The concerns about social and subsequent political impact prevailed similarly to shock therapy, but it primarily called for a slower transformation. This approach shows a trend towards a more active role of the state and firmer institutional entrenchment.[6]

It should be mentioned that theories are always influenced by their time and place of origin, and as political economics specifies, they serve the interests of certain social groups.

The Washington Consensus (WC) is a product of the 80s, and represents the start of neoliberal thinking that is a follow-up of neoclassical paradigm. It claims that it is enough to create market conditions and the system will reach an optimal state “by itself”. With respect to international economic relations, the WC aims to eliminate all obstacles, which will lead to the balancing of economic differences.

The WC, written in 1989, comprised "recipes" to overcome crises that were used in the 80s in Latin America. Its formulations were principally influenced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank (WB) and the US Department of the Treasury. It is obvious that in addition to financial interests, the WC primarily involved ideological and strategic interests. The IMF and the WB pursued new activities after the Bretton Woods system disintegrated in the 70s, and their influence strengthened significantly after the Eastern Bloc collapsed. In particular, the new role of the IMF as an international creditor of last resort, whose loans were subject to certain conditions (so called conditionality), made it a dreaded actor of international economic relations.

Leaping into a market economy, as mentioned above and connected with J. Sachs, involved implementing Western institutions quickly (i.e. shock therapy)[7], and rejecting any Third Ways and ideological ideas from the past. The WC should have rounded off the fall of the East, not only practically, but particularly from an ideological standpoint. Furthermore, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe became a laboratory (similarly to the countries of Latin America) for an experiment with "pure" neoliberal doctrine.

In brief, the WC can be summarised by three main slogans: deregulation, privatization and liberalisation. With respect to price structure, Sachs proposed maximum openness to outside competition (i.e. trade liberalisation) so that outside price structures would be established in the domestic market. The exchange rate, or its fixation (nominal anchor), was one of the tools that strongly influenced the Czech Republic, along with strong devaluation. Together with luring foreign direct investment with cheap labour, this was a short-term method of price competition with very little future potential. Furthermore, this form is not stable, because there is always a possibility (with respect to Central and Eastern Europe) to move to cheaper labour, typically to Southeast Asia. The aid of foreign managers did not work in countries like the Czech Republic, as specific local conditions manifested themselves, accentuated by the institutional economy. With respect to privatization, speed was also highly emphasised, but various forms of privatization were not differentiated sufficiently.

In general, the WC was a very simplified (according to Stiglitz, a simple and textbook-like) view of economy, which is not and cannot be homogeneous. Alone the position of international companies that control 2/3 of international trade shows the limits of considerations about the homogeneous world economy. The WC has not only become a (absolutely discredited nowadays) procedure, but first and foremost a power tool. Liberalisation suits the strong ones. The WC showed that smaller, more slowly developing countries were “forced” to accept conditions that included them in the global economy in the semi-periphery or even as outright colonies.

On the other hand, the institutional approach emphasizes institutions – social arrangement and organisation that creates a specific framework where the market economy operates. The framework of institutions modifies the forms, effectiveness and results of the market mechanism. Many forms of institutions exist: customs, traditions, forms of behaviour, ethical criteria, their codifications in laws and tools for their enforcement; furthermore there are types of companies and of course the state, its role and the functions that it fulfils.

Contrary to the WC, the institutional economy professes that the character of the enterprise fundamentally influences the character of the overall economy. Furthermore, the organisation of the market, political pressures and interests, institutional measures, the role of state, the organisation of the financial industry and capital markets, among other aspects, should be also added. Thus a completely different way of transformation necessarily results from the institutional point of view. The main aim is not to open the economy immediately, but to build up and strengthen the sphere of competitive businesses, including the system of protective measures and pro-export stimuli. Speed does not play any role – evidenced by historic examples like those of post-WWII Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia (the first wave of the so-called Asian Tigers)[8] , and currently of course the gradualist and highly successful approach of China. Moreover, the institutional approach realistically demonstrates that the experiences of other countries are not automatically transferable, and so-called path dependency or influence of previous experience and inherited conditions is always present. Nobody starts “from scratch”, from zero.

Selected questions regarding the transformation process in the Czech Republic

Firstly, we should mention that all the transforming countries underwent a shock, a so-called transformation depression. However, their depth, timing and the complex of causes were different. Poland recovered relatively quickly, but Russia was affected by a very deep depression. In general and compared to the other countries of the Eastern Bloc, the V4 was in the best position. In the countries of Visegrad Group, it is possible to determine two main reasons for the transformation depression: the application of the Washington Consensus (in Poland most of all) and the disintegration of COMECON.

Similarly, information about the financing of the transformation process cannot be omitted. There were considerations about a variant of the Marshall Plan for the East, but no willingness to fund it.[9]

All these should be understood in the context of the overall political and international context. At the beginning of the 90s, the fall of the Eastern Bloc was perceived as a great victory for the West, and there was no fear of an alternative system, a fear that doubtlessly encouraged the West to develop the social state during the post-WWII period.

The internal mode of debate: the influence of Václav Klaus

Václav Klaus’s victorious election campaign was typified by an inclination towards Milton Friedman and the concept of neoliberalism in general, though his extent of verbal support (along with the general “discussion” about a transformation way) and actual economic policy varied. Václav Klaus strongly influenced “post-revolutionary” discourse by rejecting social aspects (again: not in practical policy) and introducing a “market without adjectives”. Thus Václav Klaus followed the strong neoliberal tendencies à la Thatcher and the Polish approach, but he was not able to reflect on how Poland had undergone a significant downswing, and he later revised this policy. However, we should not forget that from a social point of view, the term “capitalism” was heard very little, and – imprecisely and euphemistically – the term tržní systém(market system) was preferred. The beginnings of the debate were also influenced by reminiscences about the Prague Spring, and the research from this period (at the beginning of the 90s) mention that the most citizens wished for a modification of the current system, something like the Swedish way, but not capitalism. The social security of state socialism was considered something that would continue, but the standard of living would increase, as would the possibilities of travel and other improvements.[10]

The undeniable charisma of Václav Klaus and his absolute self-confidence, evoking the impression that he "knows" the right way, contributed to the fact that votes looking for alternative ways (such as Občanské hnutí/Citizens’ Movement) quietened down after the lost election in 1992. Another consequence, though there were many other influences, was the disintegration of Czechoslovakia, resulting in the establishment of the Czech Republic on January 1, 1993. It should be mentioned that for a decision as critical as the country’s dissolution, no referendum was organised, though different ideas about the further, primarily economic direction, were considered to merit one.[11]

The overall debate was very polarized, as if from one extreme to the other one. According to Václav Klaus, those who were against the process of transformation were against the process as such, and were labelled (by the media, of course) as “Bolsheviks”. All efforts to correct, or to change something were denounced as something (and still are to a large extent!) “that lead us to the period before November 1989.”

Democracy started to be equated with capitalism, and with the resultant muddle of terms, one could hardly debate otherwise. From "the one and only right way", the Czech Republic set out "for the other only right way", and no doubts were admitted. Furthermore, international influence, mostly from the IMF, was limiting the debate as well as the participation of citizens in the transformation. Thus the worst from the old system was reproduced very fast – from connections and the network of contacts up to a black-and-white perception of policy and economy. It is a shame, but this has largely dominated Czech public debate to date.

Economic policy: privatization, external economic relations

Czechoslovakia, later the Czech Republic, set out on the path of applying the neoclassical model. From the standpoint of international economic relations, an undervalued exchange rate was the preferred approach (with deep devaluation at the beginning of the 90s[12]), with the so-called exchange rate cushion combined with restrictive economic policy. Unfortunately, this approach was not sufficiently reflected in the competitiveness of our companies, which therefore were not under restructuring pressure and could launch into price competition, specifically by means of so-called práce ve mzdě (hired labour). Of course, this is typical of less developed countries.

As early as the beginning of the transformation, Czechoslovakia was a more open economy compared to the other countries of the Eastern Bloc and even compared to Western countries of comparable size (such as Austria). Foreign direct investment did not play an important role during the first stage of transformation, because there were efforts to build up a “people’s capitalism” – but it is disputable whether these official proclamations were sincere or not (see below).

Foreign direct investment in the context of pro-export policy and institutional support did not see a marked increase until the post-1998 social democratic government.

However, restructuring was not possible without a clear ownership structure. Furthermore, the development of the domestic and foreign market was not clear – and companies with a new ownership structure also operated in an uncertain environment. Many companies were burdened by enormous debt (incurred in part through privatization), and owing to government policy (and higher inflation), loans were expensive.

Due to this combination of influences, the Czech economy had the character of a developing country in the first half of the ’90s. The share of machine and transportation vehicles in exports was decreasing, while the share of semi-finished products (primarily hired labour) and raw material was increasing. On the other hand, restriction and thus also inhibited access impaired the possibility of exporting capital equipment, which was later partly improved by establishing the Czech Export Bank. At the same time, the Czech economy was stimulated by the service sector (which still persists to a large extent), by the export of more complex components and the liquidation of its scientific-research base. It was obvious that without state support it is not possible to join foreign networks (the networks of global companies) – unless the companies are included based on price competition as a "service" with minimum added value.

Despite the official refusal of "social engineering", the state strongly influenced the social structure for the future, and did so through restitutions and privatization.[13]

De facto, this minor privatization only comprised buying the right of use (of a small shop, for example), so it cannot be called privatization per se. First of all, the denationalization of the retail trade network has been accompanied by enormous problems. The minor privatization created the conditions for the entry of foreign chains, which were naturally not very interested in selling Czech goods. Czech farmers and food producers have since faced major price pressure from these foreign chains.

In the case of so-called voucher privatization[14], institutional factors were yet again not taken into account. Shareholders had no influence on the operation of companies, because they neither had information nor experience with companies’ management. At first, the fragmented ownership supported the uncontrolled power of the management, which could – particularly with the right political connections – continually misuse its position. At the same time, this logically expanded the major risk of destroying the national wealth and selling it off to speculators who did not want to do business, but to make big money fast. Thus, it was very difficult to create a network of strong, competitive companies in this way, and specifically in the environment of the Western economy, where the networks of supranational companies dominate. Czech voucher privatization[15] approximated privatization to the largest possible share of the public, but it should have followed up with social ideas and played an important political role.[16] However, quickly finding owners of any kind is not the true aim of privatization – the aim is to change the behaviour of companies.[17]

An essential role was played by well-informed individuals (insiders) who knew the real situation of individual companies (and thus proved the importance of institutional economy in practice). Then there were also investment funds, very often established by banks that were, paradoxically, state-owned. Thus the overall process became more absurd.

However, the fragmented ownership and dreams about “people’s capitalism” did not last long. Concentration came about quite swiftly. The five biggest banks and insurance companies and predominantly their fourteen biggest investment companies owned more than 40% of companies’ shares from the first wave of voucher privatization, and they had an 80% share of bank loans. This is the new pyramid of concentrated economic power, administrated by a few dozen economic subjects – the board members. Probably five hundred families control the bulk of the economy without owing it. In fact, it is a new and wider “economic politburo”, never elected by largely dispersed owners, and scarcely impeachable by them. “Extreme concentration of economic power extremely separated from extremely dispersed owners – this is the present result of voucher privatization.”[18]

A very critical evaluation of privatization was published in 2013 by Klaus’s former colleague J. Stráský. Many passages from his interview for the newspaper Hospodářské noviny are very significant, such as the question whether it was intended to let the chosen ones "steal": "Of course, it was not the intention, but everyone felt unconsciously that that was the way it was. At that time it was said: It would be the best to switch off, and let the skilful ones distribute it among them. The dispute about privatization as a whole, the establishment of funds that ‘fled’ somewhere later followed the idea of accumulating capital in the hands of a few persons so that they might reach big companies. So that Škoda would not have to be given to Volkswagen, something Klaus was always against.”

And further, on the issue of bank socialism as a specific Czech way, Stráský said: "I would have to say that it was like this, and I would even say that we were aware of it. We reckoned that there was no other way than to involve banks in lending to our people. Though some will repay it, others will not. And much was not repaid, hundreds of billions had to be written off. It was likely in 1993, when the debts were cleared off to the banks, because there were also old loans that had originated during communism. It was the first 50 billion approximately. But it later came to light that during five years of capitalism they ran up ten times more debt.”[19]

Despite many negative influences, including the disintegration of COMECON or the high demand for foreign goods, the first years of transformation were positive with respect to trade. However, it should be mentioned that the favourable balance of foreign trade in 1991, for example, was more caused by the drop of import than by increased export. Devaluation worked as a special tax for import, supported by the drop in GNP. Surely, this cannot be considered a long-term, stable or desirable condition. But despite increasing inflation, devaluation necessarily exhausted itself, and gave rise to the necessity of other restrictions, which manifested itself in the so-called balíčky (packages) of 1997. Therefore it is again necessary to emphasize that the economy stabilised itself at the level of stagnation. Economic recovery shifted to the imbalance of external relations (trade balance and current account), and this imbalance culminated in the currency crisis of 1997.

First, the worsening trade balance and current account did not evoke a negative political response. Václav Klaus declared: “The alarming deficit of foreign trade and current account of the balance of payments not only need not frighten us, but are even desirable.”

The deficit of the current account with respect to the national economy expressed the discrepancy between the created product and the used product. This deep internal imbalance, which necessarily reflected itself in external imbalance, is shown in the following table:

Table No. 4: Development of internal and external imbalance

|

Indicator |

1990 |

1991 |

1992 |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

first half of 1996 |

|

Net export (% of GDP)* |

-0.4 |

7.0 |

0.1 |

-1.7 |

-6.9 |

-15.1 |

-19.8 |

|

CA/GDP |

|

|

-1.5 |

2.5 |

-0.04 |

-2.9 |

-6.9 |

|

Labour costs per unit (% of GDP) |

60 |

48 |

48 |

55 |

58 |

59 |

63 |

|

ERDI (DEM) |

4.1 |

4.5 |

4.1 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

3.1 |

|

|

Annual inflation rate (GDP deflator) |

9.5 |

47.2 |

17.9 |

16.2 |

11.0 |

11.4 |

8.5 |

* in constant prices

Source: Pick, M.: Stát blahobytu, nebo kapitalismus?, p. 47

The stabilization of the economy was not achieved at the structural level, but at the stagnation level, specifically by means of the following tools: the deep devaluation of currency, suppression of real wages and deep macroeconomic restrictions manifesting themselves not only at the demand level but also at the supply level. The repeated proposals for “rebounding from the bottom” did not have the magic effect like at the beginning of the 90s – the space for social consensus was exhausted, and at that time it was clear that society was divided between the beneficiaries of the transformation and the majority, its casualties. This fact also related to the growing popularity of social democracy, which won the election two years later (in 1998) and currently forms the minority government. Considering the preceding account, it is not surprising that the IMF’s 1996 proposals again returned to restriction as a tool for renewing the balance; i.e. the balance at the level of stagnation, like at the beginning of the transformation. Furthermore, at that time the Consolidation Bank started to de-privatize to avoid multiple bankruptcies – an experiment with voucher privatization whose costs are transferred to the state, and thereby to taxpayers.

The Czech Republic began to manifest features similar to the Mexican financial crisis (1994–1995). The inflow of speculative capital in previous years, supported by both optimistic prospects (the Czech Republic as a tiger of Central Europe) and the premature internal convertibility rushed the modification of the crown’s outdated fixed exchange rate.

Furthermore, macroeconomic restrictions foreshadowed future bank problems that "fell to" the Cabinet chaired by Miloš Zeman. The high interest margin of banks, as the economist Miloš Pick writes, many times higher than in developed countries, on one hand created reserves, but also created subprime loans. The crisis of companies had to interconnect with the bank crisis necessarily.[20]

The principal change in economic orientation was initiated by Zeman’s cabinet to lure direct foreign investment, including the concept of pro-export policy, and the strengthening or establishing of necessary institutions and agencies. Finally, the financial rehabilitation of the financial sector, costing Czech taxpayers hundreds of billions, put an end to the dream of Czech voucher capitalism. Thus the era of supranational companies’ strong influence began.

Social democracy and the arrival of the “the suicide cabinet” (vláda sebevrahů) as the prime minister at the time and the current president have labelled it, achieved a milestone in both economic and political development. The start of the Left’s rule was interpreted by right-wing media (including so-called public media) as the “return to before November”. The shift of mass media to the right has persisted up to now; in fact, left-wing mass media (besides the so-called alternative Internet mass media) do not exist.

Despite winning the election, the ČSSD (Česká strana sociálně demokratická/the Czech Social Democratic Party) was not able to find a coalition partner, and thus they made a so-called "opposition agreement" with the ODS (Občanská demokratická strana/the Civic Democratic Party). The agreement is considered the start of the government’s clientelistic policy, in particular with respect to Miloš Zeman’s cabinet, and without taking into account the connections founded back at the beginning of the 90s. For the first time, the 1998 election resulted in the rule of a left-wing party, and at the same time it confirmed the existence of two poles: the ODS and the ČSSD. Most political reporters were surprised that social democracy was able to function during the entire election period, i.e. up to 2002.

The Social Democrats won the subsequent election as well, but decided on a different, and as time would tell, unstable arrangement: a majority of 101 votes with the centre-right parties. This instability manifested itself markedly in the alternations of the prime ministers of the Social Democrats. The “grand finale” of Jiří Paroubek, the last of them, could not avert the rule of the Right in 2006, though officially the election ended in a perfect stalemate.

Ways of Integrating into the World Economy: the Way of the Czech Republic

The way of integration into the world economy is an absolutely fundamental factor, because the links between internal and external factors have their own unique dynamics, and retrospectively influence the structure of the economy and the long-term (un)sustainability of the adjusted exchange rate, the mixture of economic policies, etc.

At the beginning of transformation, all the countries of the Eastern Bloc needed imports, in particular regarding the modernization of equipment, but logically there was also a demand for Western goods, which were already being totally consumed by Western countries, above all by European countries.

With respect to the balance of payments or current account, import demand can be covered by export (depending on structure, prices and territories), capital inflow, remittances (connected with the export of labour) or foreign aid. From this point of view, it is very important to monitor the current account balance of payments. This balance has been negative for a long time in the Czech Republic, which points out a deeper structural problem.

In 1991 association agreements were signed between Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary on one side, and the European Community on the other. The association agreements were substantially wider agreements, not restricted to business issues. CEFTA, the Central European Free Trade Agreement, became effective in 1993, and pointed out the outline of the Visegrad Group – the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic, Poland and Hungary. CEFTA was intended to lead to the elimination of obstacles in trade, tariff obstacles and non-tariff obstacles. Not surprisingly, agriculture has become a big problem in the negotiation of this agreement, with Poland in particular protecting its large agricultural market.

At the beginning of the 90s, Czechoslovakia renewed its membership in GATT (Czechoslovakia had been one of its founding countries in 1947). After the division of Czechoslovakia, membership in GATT was approved for both successor states.

Institutional support, sometimes known under the name pro-export policy, is a very important aspect for determining the way a country should integrate into the world economy. However, a more suitable and comprehensive term is economic diplomacy, because export only represents one part of how a country can enforce its economic interests abroad.

With respect to the enforcement of the Washington Consensus and the neoliberal direction of the Czech government, it is not surprising that the support of investment and export (common in Western countries) was not accepted enthusiastically. Officially, exchange rate, or deep devaluation, and free trade should be "enough". This example, important for Czech economy, showed the distinct discrepancy between textbook economics, treated with irony by Stiglitz, and economic reality.

The reality of the unfavourable results of trade in the 90s, which finally resulted in the crisis of current account and in a currency crisis in 1997, required the reconsideration of neoliberal ideas. As early as 1992, EGAP, the Export Guarantee and Insurance Corporation, began its activities. Its main task, as it can be anticipated from its name, was to insure export against political risks, including reinsurance. Paradoxically only later (1995) was its "sister organisation" ČEB – the Czech Export Bank – established. Its main task was to finance export credits.

After the disintegration of PZO (Foreign Trade Company), exporters faced the problem of little information about markets, export conditions, etc. There exists an agency for this purpose in all developed countries, i.e. for rendering special information services. CzechTrade succeeded in meeting this need, but establishing it was not easy within the framework of neoliberal doctrine.[21]However, it cannot be expected that the support of government alone or the overall pro-export concept will guarantee success on foreign markets. During the transformation the structural dimensions of economy were ignored, such as the issue of involved technologies, science and research, including the above-mentioned institutional aspects, like law enforcement. It is proven that single business transactions increase opportunistic behaviour, but long-lasting relations are based on building permanent trust.

What is the current form of the Czech Republic’s integration into the world economy? As mentioned above, the Czech Republic is tightly bound to the EU. Despite the fact that we have been hearing about the necessity of diversification – both territorial and with respect to goods – for many years, no major success has been achieved. There can be no doubt that one of the reasons lies in the way the country has transformed and the subsequent response of Zeman’s Cabinet, which wanted to overcome the “solution” to the Czech economy’s poor structure through more intensive involvement of supranational companies. The accession to the EU in 2004 was another milestone, because the trade balance has been showing consistently positive results since 2005.[22] Furthermore, net export (i.e. output balance) has played a growth role in recent months, because the other components of the GDP have been decreasing.

Of course, a positive trade balance and the manner of the Czech Republic’s involvement, specifically in the European economy through its inclusion in supranational chains in the position of sub-supplier, has its risks and negative features. The most significant of these have manifested themselves in the revenue balance for a long time. As foreign direct investments “mature”, the outflow of profits from the country increases. Since 2006, the outflow of profits and dividends has been higher than reinvested earnings. Thus in this way, the country is not only losing what was created, but is also deepening its dependence on foreign influences, which might have an impact on the character of the state’s economic policy as well.

“The partial indicator of the amount we must pay for this[23] can be represented by the income balance that first of all expresses the share of foreign investors in gross domestic product. The record holders in this regard, such as Ireland, show indicators up to 20% of their GDP. The percentage of the Czech Republic is far from that, only about 5% of its GDP, but after implementing some major investments in future, its share will also exceed 10% of its GDP.”[24]

The highly negative income balance (in 2012, almost 290 milliard Kč) has caused that the current account as a whole is in the red. It is true that the negative balance has not reached critical values (in relation to GDP) as it did in 1997, but it points out the fundamental structural weakness of the Czech economy. This negative balance of the current account is covered – as mentioned in the introduction to this part – by not being directly associated with arising crisis, but by the inflow of foreign direct investments, as well as in the form of reinvested profit. In this way, the Czech economy has found itself in a vicious circle – negative current account – covered by the financial account (FDI) – further outflow of profits – ???

The main bearers of FDI are the Netherlands, Germany and Austria. However, with respect to the Netherlands, it should be specified that these companies are not Dutch companies, but ones that use the Netherlands as a unique tax haven. In many cases, they are originally Czech companies that have transferred their registered offices to the Netherlands.

“The weaknesses connected with the entry of FDI predominantly related to the pre-privatization stage in the financial sector, when the Czech state, before selling its shares to foreign investors, financially rehabilitated its biggest banks, either in the form of transferring dead assets, or in the form of providing guarantees. This financial rehabilitation cost hundreds of billions of crowns. The other matter in dispute is the partly revised[25] character of the production under foreign control that is more observable in its production and intermediate consumption share than in the sector’s gross added value.“[26]

Table No. 5: Current account* and income balance/GDP ratio by %

|

Year |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

CA/GDP |

-2.0% |

-4.3% |

-2.1% |

-2.4% |

-3.9% |

-2.7% |

-2.4% |

|

Balance of revenues/GDP |

-4.9% |

-6.9% |

-4.5% |

-6.6% |

-7.5% |

-6.6% |

-7.5% |

A CA deficit/GDP ratio of 5% or more is considered to be a limit value. The Czech Republic exceeded this value significantly in 1996, for example; i.e. before the 1997 currency crisis broke out, which resulted in the abandoning of the fixed exchange rate.

Source: Czech Statistical Office: Macroeconomic indicators + Czech National Bank (round)

The period since 2006 has been linked with right-wing governments. While the election in 2006 ended in a perfect stalemate (100 votes for the Right, 100 votes for the Left), Topolánek, the prime minster at the time, later “provided for” the so-called defectors, and in the 2010 election the Right won by an overwhelming majority. In the years leading up to it, the Right was able to dictate public discourse, which was particularly directed towards the allegedly excessive extent of public services and their ineffectiveness. Then in the 2010 election, public debt was a key issue, illustrated by the case of Greece, and there is no doubt that it won the election for the Right. The Left, predominantly the Social Democrats, held a defensive position, also caused by the collapse of the so-called Third Way which had been so trusted at the beginning of the 21st century. Despite the fact that the Social Democrats won the 2010 election by narrow margin, it was a Pyrrhic victory, because they were not able to form a coalition.

The clear victory of the Right – which subsequently began to face the break-up of the shady party “Věci veřejné” and many scandals – mobilised civil society, which had thus far been nearly invisible, expressing itself only rarely and in spurts. However, it was not able to perform continual activist and professional work. After 2010, the boom of civil pressure was visible, but it was very often ineffective and diffuse. Many civic initiatives and movements were established (Proalt, Alternativa Zdola [Grassroots Alternative]), pursuing new topics (Hnutí za přímou demokracii [Movement for Direct Democracy]), and the most successful initiative fighting against the American missile defence project – Ne Základnám/No to the Bases – came to life. Society became more active; predominantly the left parties tried to cooperate with civic initiatives more than before, and trade unions also participated. The threat to the social state, despite the sharp cuts of Minister Kalousek (see below) united many, very often disparate parties. In April 2012, more than 100 000 protesters met at Wenceslas Square – but without any political impact. Strong civil resistance was evoked by so-called church restitution, which made the Catholic Church the largest land owner in the Czech Republic. The first direct election of the President was another turning point, won by former prime minister Miloš Zeman. He has been an active president from the beginning – as he promised during his election campaign.

Current Situation: Convergence or Divergence?

The Czech Republic’s economic growth (in terms of GDP) between 2001 and 2010 was 3.4% annually on average, which was more than the average of the EU27. The Czech Republic achieved maximum growth from 2005 to 2007. Of course, the country was affected by the crisis, and the economy slowed down at the end of 2008 markedly. Despite the “expectations” of Minister of Finance Kalousek, who proclaimed that the crisis would not affect us, it did – not through the banking/financial channel, however, but through the economic channel that is predominantly export-oriented. The GDP in 2009 dropped by 4.7%. The subsequent divergence of the Czech Republic is caused by domestic factors, primarily by extreme fiscal restriction. This restriction resulted in a major drop in household consumption that can be only compared with the countries undergoing debt crises. Unlike its neighbours, the Czech Republic has not reached the 2008 level; recession has continued, and during the first quarter of 2013 it was -1.9%.

Graph No. 1: GDP of the Czech Republic, 2008/first quarter 2013

The Czech Republic’s convergence process is typified by the gross national income (GNI) being lower than the gross domestic product (GDP), as mentioned in the previous part and shown in Table No. 5. As mentioned in Konkurenční schopnost České republiky 2010–2011 [Competitiveness of the Czech Republic 2010–2011][27], the Czech Republic was among the countries with the biggest primary income outflow in previous years. This loss is not only virtual, because it has an impact on final consumption and savings. A less favourable, but more realistic view is offered by the analyses of “net” indicators such as net product and income. The consumption of fixed capital has grown faster than the GDP (which predominantly results from the industrial character of the Czech Republic), and thus the net national product has increased more slowly than the GDP.[28] Therefore, we can see that just a simple look at the GDP is not sufficient for the purposes of evaluating convergence.

From a macroeconomic point of view, the Czech Republic is typified by several peculiarities[29] – one the one hand, a quite low proportion of private consumption, hovering at about 50%.[30] The individual consumption of the government has also been quite low compared to developed countries. On the other hand, a more vital role is played by external economic relations. In the post-crisis years, it is foreign trade (output balance) that has been the sole growth component. As was proved in 2012, the slump in domestic demand resulting from severe fiscal restriction reversed this positive momentum.[31] Foreign indebtedness has started to increase and in the stagnation years, the level of 40% of the GDP was exceeded.[32]

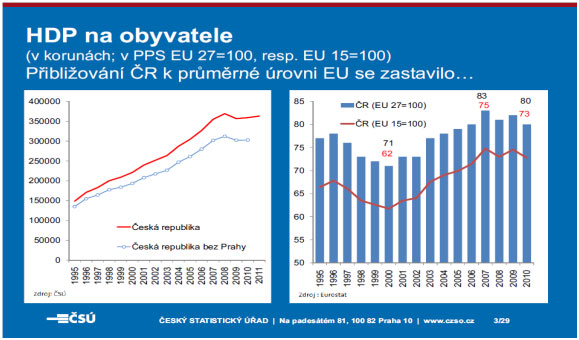

How does Konkurenční schopnost České republiky 2010–2011 [Competitiveness of the Czech Republic 2010–2011] evaluate the convergence of the Czech Republic? While the slump at the beginning of the 90s (the so-called “transformation shock”; see above) was a common feature of transforming economies, the Czech Republic survived another slump at the end of the 90s, together with a smaller currency crisis in May 1997, followed by a banking crisis. However, these problems clearly resulted from the insufficiency of the transformation process, either the fixed exchange rate as a nominal anchor in the situation of real appreciation (exchange rate revaluation), or the inappropriate privatisation and the insufficient restructuring of the Czech economy. With respect to the EU15, the initial economic level was only overcome in 2004! Convergence towards developed countries was soon interrupted by crisis, and also by the inappropriate economic policy of the right-wing political parties, specifically by Neča’s Cabinet; i.e. by excessive fiscal restriction. The current situation of the Czech Republic’s convergence, measured by GDP per capita and purchasing power parity compared to developed countries is cca. 75–80%(see Chart No. 2). However, it should be mentioned that there exist deep regional differences, and the position of Prague is absolutely exceptional. According to the analyses of the Czech Statistical Office (CSO), GDP per capita at power purchasing parity increased in Prague by 40% compared to the EU27 from 1995 to 2010; outside Prague, it only increased by 0.8%! This huge difference is not sufficiently reflected in regional or structural policy.[33]

With respect to the use of labour resources, the Czech Republic is above average, but we should not forget that specifically in recent years, the share of untraditional employment contracts has increased (self-employed persons – casualization, contracts for limited periods of time, and others), which has a negative impact not only on the social situation, but also on public budgets. Poverty has been also increasing, including so-called working poverty – which predominantly affects women.

As far as nominal convergence is concerned, which we express based on the price level, and which is of course linked with real convergence, the Czech Republic has two channels at its disposal: the price channel and exchange rate channel. Compared to the EU15 average, the price level has reached approximately two-thirds. There are of course significant differences among goods. For example, while some food and consumer goods are cheaper on the German market, the price levels of machines and equipment is equal. On the other hand, major price differences persist in public services. The wage level lags behind the price level even more. Thus, the analysis concludes with respect to the concept of competitiveness that the Czech Republic remains at the effectiveness stage. First of all, cost pressure, or cost competitiveness, depends more on low wages than on the exchange rate. It is also probable that the way the Czech Republic is integrated into the global economy, and particularly the European economy, does not allow it enough space to increase wages, keeping it under wage pressure and overall cost pressure.

With respect to competitiveness, we mentioned above that the Czech Republic remains at the effectiveness stage, but the number of countries competing with prices is increasing. The countries that integrated into the global economy earlier based on simple labour with minimum added value have been advancing higher (many countries of Southeast Asia, China, Latin America). According to the CSO document Česká republika v trendech [The Czech Republic in Trends], the country’s share of global exports is on the decrease. This might indicate that the Czech Republic is not able to keep up with the development of many dynamic markets, and it could support the proposition about the country’s excessive focus on the European market. At the same time, the Czech Republic is losing its cost competitiveness, which according to the report should not be seen as a purely negative phenomenon, because in the long run competition by means of cost creates pressure to decrease the standard of living. Inability to advance to the innovation stage when the cost competition stage loses its potential is expressed, for example, by a low proportion of workers (one-third) in jobs demanding knowledge. The under-financing of science and research has been discussed for a long time.[34] Though the gap between the Czech Republic and the EU15 has been decreasing in tertiary education, specifically with respect to “younger” differences, we should analyse the level and utility of this education, and whether it matches the needs of Czech economy.

We conclude that it is not typical that the basic indicators of convergence are so different. A major topic for discussion is why there is, in relation to Germany, for example, such a big difference between economic productivity (cca. 2/3) and the level of wages (cca. 40%). It is justified to ask where those 26 percentage points are.[35]

Chart No. 2: Convergence of the Czech Republic

Conclusion

“In comparison with the other transition countries of the central European region, the Czech Republic took a remarkable lead in productivity. It had low foreign debt, a rather minor imbalance on the domestic market and very low inflation. The accumulated civilisation potential – an educational and qualification level typical of adaptability to a large extent, was its “comparative advantage” for many years. These advantageous initial conditions of the Czech Republic have not only been used improperly, but have also to no small extent been wasted.”[36]

Corruption at all levels (starting from the municipal level up to the highest level of government) and so-called rent-seeking that very often takes the form of laws tailored to certain groups, most often financial ones, are among the main political and economic issues perceived by the Czech public as a thorny problem.

As far as political development is concerned, the Czech Republic has proceeded from overwhelming enthusiasm resulting from a mass movement (the Civic Forum) at the beginning of the 90s up to its disintegration into more or less standard political parties. This development was dominated by Václav Klaus, who not only initiated the economic way of transformation, but also an extremely rightward-leaning political discussion. Topolánek, the previous prime minister of the ODS, had a strong inclination towards the vocabulary of the Third Reich (es kommt der Tag, he promised journalists, of “the Night of the Long Knives”, etc.). This deviation has since persisted. The Left is still interpreted as a second-rate political stream despite the strengthening of the Social Democrats in recent years. The strength of public anti-communism, supported vehemently by the mass-media, is one of prominent features of recent developments, increasing rather than decreasing as time passes since the “revolution”. This shows that Czech society, with respect to its political culture, is focused on addressing bygone problems, and it is unable to effectively respond to or cope with current problems or changes in the global economy and international relations.

The current scandal of Nečas’s Cabinet (ODS), linked with the misuse of the military secret service and huge corruption affairs, has resulted in a Czech society that is more and more fed up with politics. This is reflected in an increased call for direct democracy as a universal solution, which certain populists (e.g. Senator T. Okamura) have seized as an opportunity. The voices demanding a “powerful leader” can be heard more frequently, and society has been markedly receding from the politically liberal and open 90s. The conservative tendency and exclusion has strengthened. Social exclusion is a strong new trend in the political culture and relates to various groups, most of all to the Roma, and the situation in the northern Czech Republic is particularly tense in this regard. Exclusion also relates to homeless people, seniors and migrants. Society more and more discusses the issue of “parasitization” – a discourse presented by the Right alleging a wide massive misuse of social benefits pervading society as a whole.

Furthermore, with respect to the main political parties, the scene cannot be considered stable. New movements and political parties are emerging, responding to social demand and distaste for current developments. Surely, the directly-elected President Miloš Zeman will play an important role in this socially unstable situation. The civil sphere, thought more active since 2010, has remained heterogeneous and too disorganised to influence policy more – with the exception of certain individual cases and topics.

The publication Česká demokracie po roce 1989 [Czech Democracy After 1989] states in its conclusion: “Contemporary Czech democracy faces many problems: in particular the corruptibility of political parties; the remoteness of the political elite, rejecting whoever wants to change it too much, thus causing the elites to distance themselves from the citizens’ problems; unstable, poor-quality, ineffective and notably politicized state administration; certain politicians excessively expanding the competencies of constitutional bodies; the doubting of the role of decisions by the Constitutional Court; an insufficiently developed civic society and the considerable prevalence of political apathy in society; the tendency of mass media to be strongly influenced by politicians; and more.”[37] Therefore the transformation has not been completed, at least with respect to the political situation.

Bibliography:

Bureš, J., Charvát, J., Just, P., Štefek, M.: Česká demokracie po roce 1989, Institucionální základy českého politického systému, Grada, 2012.

Dale, G (ed.): First the transition, then the cash, Eastern Europe in the 2000s, Pluto Press, London, 2011. Dubská, D.: Ekonomika ČR v trendech: byl rok 2011 opět zlomový?, ČSÚ, 2012

Dubská, D.: Firmy se zahraniční majetkovou účastí v ekonomice ČR: oslabily nebo dále sílí?, ČSÚ, 2012.

Klvačová, E., Malý, J., Mráček, K., Dostálová, I., Chlumský, J.: Státní pomoc, nebo dobývání renty?, Professional Publishing, 2005.

Kolektiv CES VŠEM, NOZV NVF: Konkurenční schopnost České republiky 2010-2011, Praha, Linde, 2011.

Kubišta, V. a kol.: Mezinárodní ekonomické vztahy, Praha, HZ Editio, 1999.

Myant, M., Drahokoupil, J.: Transition economis. Political economy in Russia, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Wiley, John Wiley and Sons, 2011.

Pick, M.: Stát blahobytu, nebo kapitalismus? My a svět v éře neoliberalismu 1989-2006, Grimmus, Všeň, 2009.

Prorok, V.: Tvorba rozhodování a analýza v politice, Grada, 2012.

Štouračová, J. a kol.: Proměny ekonomické diplomacie v ČR a ve světě, Praha, Professional Publishing, 2012.

[2] Properly speaking, Western left-wing politicians in particular use the term state capitalism, because they are of the opinion that after 1948, the system of Eastern Bloc deviated from its theoretical bases, outlined by K.Marx first of all, and that it is not proper to label it as "socialism". There is even growing confusion resulting from the fact that for example the current system of China, and partly the system of other developing economies, is denominated as a state capitalism.

[4] The degree of state ownership, or compulsory cooperatives, varied from country to country, but it was extreme in Czechoslovakia. This is important to understanding later "discussions" about the form of transformation.

[5] It was this very system that did not allow for a qualitative turnover in the ‘70s. It may have been effective for the massive mobilization of resources for post-World-War-II reconstruction, but it was not able to revise itself.

[6] The EEC, and later the EU, had a wider agenda compared to the Washington Consensus, which was restricted in its context as well as being economically unilateral. The 1991 Association Agreements testify to this. However, there was not clear support for the Washington Consensus, there were references to social cohesion, and the EU at that time, under neoliberal pressure and looking to find its own way, was not able to offer a specific model as an example – such as a social state (though declining at that time), and the social dimension was very weak in general.

[10] These topics also include a conflict that will probably never be resolved satisfactorily, to the extent that the “Velvet Revolution” comprised a political aspect – democracy, freedom, the possibility of elections, travelling, and what was the extent of the economic aspect – increased standard of living, “to be as affluent as people in the West” and others.

[11] The pressure to divide Czechoslovakia also had its economic implications. The Czech part was not willing to transfer finance to support a weaker Slovak part, because Czechoslovakia was, in its own way, a monetary union. On the other hand, according to Václav Klaus, structurally weaker Slovakia could not bear the reforms.

[12] In 1990, three serious devaluation were brought about, the nominal value of the Czech crown dropped to 57% of its 1989 level. The exchange rate became deeply undervalued against purchasing power parity (expressed by the coefficient ERDI). But thanks to higher inflation, this undervaluation, the so-called exchange rate cushion, was quickly exhausted.

[14] It was ironically commented on as the achievement of the status that the previous regime would have liked to achieve: all the companies belong to us all. There were 8.6 million so-called DIKs (držitelé investičních kuponů/holders of investment vouchers). With respect to the risks of voucher privatization, Miloš Pick cites the old joke: “it is not only unable to fulfil expectations, but it also cannot address the problems that it itself gave rise to.”

[16] Miloš Pick considered the sale of shares, acquired thanks to voucher privatization, to be a significant social cushion

[22] [22] Nevertheless, there exist significant differences within the framework of foreign trade’s methodology. According to foreign statistics, the Czech Republic shows markedly higher positive balances, but according to the national understanding, the balances are much lower, raising the question what the “real” trade balance of the Czech Republic and its real impact on the GDP are.

[23] The lecturer Chlumský mentions that we pay dearly for backwardness; i.e. countries pay dearly (in a neo-colonial manner) for not being developed enough. One of these ways is represented by the outflow of earnings, and further by the suppression of labour prices or exchange rate devaluation and exchange rate deviation from power purchasing parity expressed by the coefficient ERDI.

[24] Currently, income balance (deficit) is cca. 7% of the GDP. This type of paying for backwardness has been increasing, exactly as Chlumský presupposed.

[29] From a microeconomic point of view, for example, these would include a bigger share of industry in both the GDP and employment.

[32] However, in comparison to other transforming countries, it is very low. It should be also added that with respect to so-called complex indebtedness; i.e. the debt of governmental sector and private sector, the Czech Republic belong among the best countries of the EU. the second place after Romania.

[33] By percentage, Prague reached 172% of the EU27 average, other regions only 67%. Dubská, D.:Ekonomika ČR v trendech: Bude rok 2011 opět zlomový?, ČSÚ, 2012

[35] We would like to thank the D. Choma, Professor Emeritus at the Prague University of Economics, for drawing our attention to this substantial disparity