The role of National Development Banks (NDBs) has been rising worldwide since the financial crisis, the global supply chain crisis, and among growing geo-political tensions. Unlike EU member states, NDBs in the European Union aren’t subjected to Maastricht austerity criteria and may thus offer a major tool for the transformational policies we need.

Source: Bicanski, Pixnio (CC0)

Contents

Introduction

The rise, fall, and resurrection of NDBs

Main goals of NDBs: more and better investment

Table A – Economic development goals

We sum up the issues stemming from our analysis of rationale and aims behind NDBs.

Table B – Possible critiques to NDBs

Main characteristics of NDBs

We need bigger NDBs

An NDB democratic governance structure is possible

Banking supervision

Funding – the most important part

The deglobalisation issue

Pricing and profitability

Connection with fiscal policy

Conclusions

References, Appendix, Footnotes

Introduction

Great defeats discourage people for a long time – L. Trotsky

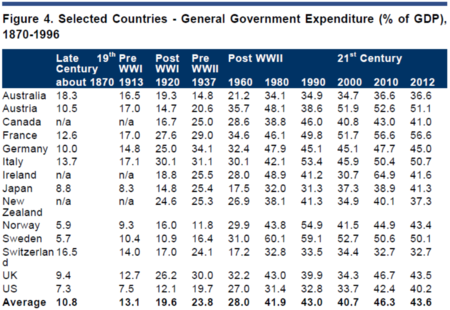

In the last fifteen years, the world economy has been shaken by at least five major events: the global financial crisis of 2007-2009, the euro crisis of 2011-2012, the pandemic, the climate change and now the war in Ukraine. These events are already shaping the world and this polycrisis will most probably deepen in the foreseeable future. The most striking feature of the world economy today is the structural low growth (World Bank, 2020). A factor behind this slowdown is connected to the difficulties of overstretched global supply chains (GSC), as it became abundantly clear during the pandemic and since Russia started its war against Ukraine. Globalisation as we have known it for decades is basically over. What will take its place is very difficult to predict, although what is certain is that States and their national governments will have a by far bigger role in the economy. The narrative of laissez-faire was only a myth even during the golden era of the Thatcherite policies, because in reality the overall weight of the State has not receded (see the following graph):

(Buiter and Rahbari, 2013)

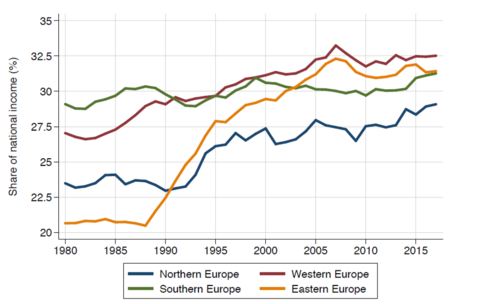

However, if the dimension has not changed significantly, what did change was the direction of the State intervention. After WWII, the welfare State was meant as a tool for redistributing wealth and hence also as a tool for higher growth due to higher aggregate demand, more human capital accumulation, etc. After the 1980s, the role of the State was focused on helping firms’ profitability in many ways: more taxes on labour and less on capital, pension funds instead of public pension, free flows of capital among countries, privatisations of public services, opening of new markets (for instance in the old Soviet bloc) both for cheap labour and for new customers, and so on. It is difficult to determine if this strategy has worked because effects differed between countries. More advanced countries have seen a stagnation of wages and a concentration of wealth and income even before the turmoil of the last years. For instance, see the following graph:

(Top 10% income shares in European regions; source: wid.world/europe2019)

The turn in the role of public policy also affected regulation: every public function had to be shaped by profitability, including laws. Labour market laws have been changed to destroy unions, fiscal laws have been changed to make it easier for the companies to avoid taxes (tax havens, “fiscal optimisation”, etc.), financial regulation has been changed to become “market friendly” or “light touch” as they called it. As we observed, these efforts produced a strong increase in the profit share on the national income, wealth, and income concentration, and a strong increase in the dimension and profitability of banks and other financial operators.

Neoliberal policies (“Washington consensus”), could be seen as a symptom of the modern importance of financial markets. However, although it is true that financialisation has been strong in the last decades (Palley, 2007), this mindset is nothing new. Indeed, “laissez nous faire” has always been the default option for economic policy in Western countries. Just to give a quotation from exactly a century ago, the Finance Commission at the Genoa International Economic Conference of 1922, which discussed how to reshape the global financial system after WWI, stated: “We are of the opinion that any proposals to interfere with freedom of the market for exchange, or to violate the secrecy of bankers’ relations with their customers are to be condemned” (VV AA, 1922). Not even the bloodiest war on human record had convinced the Western economic experts of the time that something had to change. Even after the 1929 economic depression (worsened by the 1931 banking crisis) governments were hesitant, including Roosevelt who was elected with the promise of balancing the budget. It is true that on the financial side, Roosevelt and other Western leaders were forced to use financial repression to save the day, but what changed the economic situation, allowing unemployment to evaporate, was the preparation of another world war.

After 1945, the need for Europe’s reconstruction, the Cold War, and the strength of the labour movement in the West helped to keep a wide role for public policies on many fields. This was true also in the financial markets, where for 30 years financial repression prevailed and prevented financial crises. However, from the end of the 1970s to the first years of the 1990s, it all changed. In the financial markets, laws like the Glass Steagall Act and the Italian Banking Law of 1936 were repelled, banks were left free to operate as they wished, capital controls were scrapped, and central banks were made independent from the government. Hence, they were left free to only care that what is called “asset inflation”, i.e., wealth concentration, did not result in inflation tout court. The growth of financial assets was not an issue as long as other prices were not growing too much, especially wages. Because of having freed the “animal spirits” of big financial operators, frequent financial crises ensued: the demise of the EMS in 1992, Mexico 1994, Asian Tigers 1996, Brazil, Russia and LTCM in 1997-1998, the dot-com bubble in 1999-2000, etc., until the biggest of all in 2007-2009. Every crisis was stopped throwing public money to banks and financial operators, and yet the crises’ explanation was that markets were not free enough, firms have still too many constraints, etc. However, the global financial crisis was so big and forced the governments to such a fiscal effort to tame the panic that something had to be done. And yet, what ensued in terms of financial re-regulation has not changed anything fundamental. In fact, with the Euro crisis a couple of years after and also with the pandemic, States and central banks have been forced to intervene again to save the banks. In 2023 we have seen new bailouts, for instance with Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse (Luca Lombardi, 2023).

As far as the financial system is concerned, although many supposedly rock-hard truths have been melted away by the events, they have not been substituted by a different model, rather they have been patched up by some quick fixes which have only delayed new crises. Rules have been made stricter, some exaggeration has been put aside, but the general framework in the financial world is still that markets, i.e. big banks, know better and are better left alone (Mastromatteo and Esposito, 2016). Therefore, it is important to underline that liberal policies are not the consequence of a doing nothing approach by policymakers; on the contrary, economically liberal governments remain constantly pro-active to allow private enterprises to operate freely, i.e. producing wealth for the rich.

This quick introduction was aimed at shedding some light on two points. The first one is that in this work we are not advocating that the governments should necessarily do more of what they already do, for instance in terms of financial resources; perhaps this could be the outcome of the analysis, but it is not the key point: what we are proposing is a different set of aims for public policies, a different direction, not a different dimension. The second point is that it is useless to wait for a self-reform of the financial system, neither will it ever deeply change by only applying a few superficial new rules. A different financial system, able to foster a green transition, social fairness etc., can only be imposed by the government to banks and financial operators during a bitter and prolonged political struggle.

The rise, fall, and resurrection of National Development Banks

The first line of intervention of modern States in the financial system has been using the central banks. Although central banks do not normally invest in specific sectors, with the QE policies they were forced to buy and hold financial assets for years, including corporate bonds. However, these assets were bought to help the banks in various ways and were not meant as a way to increase investment in specific sectors. In a similar vein, in the 1920s Bank of Italy was forced to hold stocks of many firms coming from the crisis of private “mixed” banks before the creation of the IRI 1 . Due to the economic and political crisis in the 30s, the initiatives by the Soviet government to mobilise all the financial means to industrialise the Soviet Union were studied in the West. These initiatives can be considered a forerunner of the role of national development banks (Carr and Davies, 1969, ch. 29). Of course, USSR public banks were part of a centrally planned economy, so their role could not be replicated in toto in a market economy. At any rate, after WWII, many governments in capitalist states founded national development banks (NDB) or used State-owned banks to pursue industrial policies. From the 1980s to the end of the 1990s, most of these banks were privatised. This is especially so in Italy and France where State-owned banks were particularly important. For years, the share of the banking system still in public hands was a proxy for cronyism and backwardness — according to the neoliberal dogma. Ironically, while the experts from the most advanced financial hubs were lecturing developing countries’ public officers on the importance of rapidly privatising the remaining State-owned banks, the great financial crisis smashed the planet, forcing the government of the advanced countries to nationalise or to rescue in other ways their banking system.

It is true that this kind of nationalisation is only “socialism for the rich” as Roubini, Reich, and others put it ” (for instance Reich, 2019; Sanders quoting Martin Luther King, 2023, etc.), in the sense that it is not based on long-term strategies but only on the immediate need of the banks for cash: nothing has changed for nationalised banks in terms of business model or any relevant behaviour. However, when after the 2007-2009 crisis other crises ensued, it became clear that a more structured public role in the financial sector was needed. This explains why “both the size and the number of NDBs have increased dramatically over the years” (Volberding, 2016). Things have changed indeed: “There are today 910 public banks worldwide that command $49 trillion in assets… And public banks are on the rise. Not only have bank privatisations stalled but governing authorities, north and south, are creating new public banks” (Marois, 2021, p. 4). Since 2018, the amount of total assets of the public banking system has increased by 7 trillion. Even if public banks from China or India are now important on the world scale (in 2022, the first four banks for total assets on a world scale are Chinese State Owned Enterprises (SOEs)) still most of the public banks are from OECD countries, particularly from Europe 2 . As for multilateral banks, in 2020 they were 77, with combined assets of $4 trillion (Marois, 2021, p. 53). However, the fact that the largest of them is the European Stability Mechanism speaks volume.

With the crisis of the global supply chains (GSCs) and the growing geo-political tensions, the NDB role is definitely on the rise. Keynes ends the General Theory with the famous final chapter on his social philosophy proposing a high degree of investment socialisation. We think the idea is right and the most efficient tool to this end is an NDB.

Main goals of National Development Banks: more and better investment

Broadly speaking, the role of the NDB is now widely accepted; therefore, it makes sense to discuss their potential specific role in a country’s development and financial strategy. We start discussing the rationale behind their deployment in the coming years and the goals they should have.

In the last decades, advanced economies have experienced a reduction in economic growth. One of the main reasons of this decline is the reduction in private and public investment (see the following graphs):

(Sandbu, 2022)

To reverse this trend, government and central banks have used market tools. For instance, they have reduced interest rates, taxes, indirect labour costs, etc., to no avail. On the contrary, they only succeeded in fuelling financial bubbles and job precarisation. For more than two decades, low interest rates have prevailed, helping States, families and firms to service their growing debt. The problem is that since 2021 inflation has risen and in some OECD countries it reached levels not seen since the 1980s. This has pushed central banks to tighten their policies, thus making life more difficult for debtors. The frequent financial crises have shown unequivocally that banks and asset managers do not have particular clues on which borrower is likely to repay their money. This is not the case because they are not able to assess the counterparty risk at the micro level. On average they are. The problem is that they follow the trend, creating waves of overinvestment in one sector after another and, when the bubble bursts, even good counterparties are not able to pay back their debt (Keynes with the beauty contest and Minsky with the financial instability hypothesis explained this mechanism very well). A second point is that financial markets only care about profits, as it is natural. So, public services that are important for long-term economic growth, such as education or healthcare, but do not yield immediate profits, are not interesting, unless their fares go up so much that a large part of the population is excluded, as it is the case in the US. In Europe the situation is better but the trend is a two-tier system: private operators take the interesting part of a market (high speed trains, post-graduate education, pension funds, etc.) and the public is left with the less profitable parts. Then laissez-faire economists find that private operators are more profitable! This already bad situation is worsened by the austerity measures that cut universal public services.

The explosive recent growth of “green finance” could be considered proof that even greedy private operators are keen to join the fight against climate change. In reality it is quite the contrary. First of all, we still have a wide funding gap for the green transition, a further confirmation that the financial system does not automatically select the right investment but only what happens to be profitable in a given day, from subprime mortgages to cryptocurrencies. Secondly, private finance started to enter the green finance scene when it was clear that the States were pouring in so much money into the transition that strong profits were coming. The 110% bonus in the building sector in Italy is a typical example (Giuffrida, 2023) 3 . Finally, single green projects are not useful if they are not part of an overall plan for the transition and they must be considered as a whole, something that lenders cannot do and are not interested to do. To ensure a strong and general intervention in green finance and more generally in the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs), what is needed is a direct intervention through a public operator. As the NDBs’ broad role is nowadays clearly understood (see the following table for a synthesis), we can move on to their specific aims.

(Nyikos, 2017)

Scientific literature and historical experiences show that there are two main sets of goals for an NDB. On the one hand, there are objectives in terms of development (overall development, the development of specific sectors, areas, etc.), on the other hand, there are objectives in terms of financial stability and the functioning of the financial system. Let’s see them in turn (for a general discussion on the topic: Bassanini et al., 2014; for a survey, WB 2017).

T

| Table A – Economic development goals | |

| The goal | Discussion |

| 1.A Identifying and selecting all-purpose investments, or investment for specific sectors (energy, transport, ICT) and projects to enhance structural productivity and to transform the economic landscape of the country. | It is now widely accepted that there are investments able to increase the overall productivity of a country, but which are not interesting for private investors (banks, asset managers, venture capitalists) that only accept risk when it is short term (Mazzucato, 2013). This for two main reasons: a) the investment has a too long-time horizon and is uncertain for a private investor’s viable strategy; or b) the appropriability of the results of the investment is low. This determines a funding gap (for instance in the financing of the green transition, of the public services or of infrastructure) that is normally and inefficiently addressed using fiscal tools (carbon taxes and subsidies, etc.). A public bank is the quintessential patient investor and could fill this gap. An NDB could provide medium- and long-term capital for productive investment also accompanied by technical assistance (as the European Investment Bank already does). As for specific sectors, the crisis of the GSCs due to the pandemic and then the war has opened up a discussion on the so-called reshoring 4 . Only an NDB can intervene to reshape an entire supply chain, whereas private investors only care about a specific segment of it. |

| 2.A Developing a thorough industrial policy, not reducing it to subsidies for private firms. | The key role of an NDB to foster investment and specific industrial projects also allows for the rebirth of a true industrial policy. In mainstream economics, markets are efficient and their outcome in terms of income distribution and commodities production and consumption is the best possible due to the invisible hand. If this is not the case, it is because there are imperfections that affect the markets such as information asymmetries, negative externalities, sunk costs, and so on. The aim of public authorities is to remove these imperfections to let the markets operate freely. For instance, if there is unemployment it is because there are unions, minimum wages and so on. If the government frees the firms from such obstacles, labour demand will increase until full employment. This means that the only acceptable public policy is to correct market failures (Mazzucato and Penna, 2016). The public role is therefore reduced significantly because public authorities must show not only that there is a market imperfection but that their policy is able to eliminate it. Strong uncertainties of very long-term investment, especially in new projects, explain why new sectors are created by public investment either directly or indirectly. In this sense the role of NDB can help innovation (Clò et al., 2020) and the overcome of already established firms that dominate a sector using technological lock-in effects and network effects (Katz and Shapiro, 1985; Liebowitz and Margolis, 1995) 5 . |

| 3.A The strategic dimension: defending and expanding the core values of the EU. | The EU has put many social and political goals at the core of its agenda (starting with the fulfilment of SDGs and the green transition). However, the Lisbon Treaty framework and more generally the EU rules keep these goals on paper only. Private operators are uninterested in social goals and SDGs in particular, except for the few cases where profits are high and certain, as with some green projects. In the specific EU situation, NDB-financed industrial policies can rebalance the Maastricht Treaty framework where austerity and laissez-faire have been ruling and public banks have been marginalised, even in Germany (Volberding, 2016). They can become the financial arm of the EU social policies (social inclusion, sustainability, and so on). |

| The economic development goals | Discussion |

| 1.B Providing counter-cyclical finance to stabilise the economy and tackling the credit crunch, reducing the importance of private-owned banks (supporting a more democratic finance). | Financial markets and credit markets in particular are highly pro-cyclical: banks and financial operators lend too much in the upswing stage of the bubble and they escape when the bubble starts to crumble, producing credit crunch and a more painful recession. NDBs can stabilise the situation. A bigger role for public banks not only allows for a reduction of banks’ myopia and markets short termism (as observed already by Minsky, 1996), it also allows for a more inclusive and democratic finance, because resources are mobilised for long term general aims and not for immediate speculative results that are counter-productive even for private finance after some months. |

| 2.B Providing financial services in sectors or regions that private financial intermediaries do not serve sufficiently. | Financial operators are not interested in providing services at a loss. For instance, banks are closing branches in small towns because they are less profitable than the branches in the main cities. Although there is a transition towards digital-based financial services, many customers would like to have the possibility of choosing the traditional “physical” bank. Only because they live in a small town, they are excluded from this possibility. The same is true for specific niches of the market, specific products and so on. It is true that the cost of providing these services is different, say, in a mountain village of the Alpes than in a district of Rome or Berlin, but it is logical that the customers of the big town pay a tiny fee to allow banks to bring the services to everyone. This is true for every general service, like electric power, phone services, heating etc. It is obvious that if a family living in the Alpes should pay for the true cost of having the electricity lines to its doors, it could not afford it. Private operators can rationally select the sectors of the market that are interesting for them, even if it means excluding part of the population or they are heavily subsidised by the government. Only public operators can solve this issue: in fact, when in Italy, public utilities like energy (electricity and gas), water and phone networks were public entities (SOEs, municipal public companies etc.), they were managed as universal services. Without public intervention in these sectors, a large part of the population would be excluded from these basic services because these layers of the market are not profitable. Otherwise, they will be much more expensive to everyone. |

| 3.B NDBs create a more diverse financial system. | When the global financial crisis hit the world, many commentators underlined that financial concentration, herd behaviour and other factors enormously reduced the diversity of banks and financial operators. As Haldane (2009a) observed: “In essence, the financial network has over time become progressively more complex and less diverse”. The marginalisation of cooperative banks and public banks played a decisive role in this process. After the crisis, more mergers and concentration ensued; therefore, diversity in the financial sector is even lesser than before 2008. There is no private solution to this issue because the only way to bring back more diversity is to reduce the role of private financial operators and their vagaries. NDBs can allow governments to partner with financial intermediaries on a fairer foot, thus developing a joint vision and expertise to fund projects in strategic sectors. A bigger role for NDBs could also help a general reduction of the weight of finance on the economy, which has been considered too big even by the IMF (Arcand et al., 2012). |

The economic development goals

Discussion

1.B Providing counter-cyclical finance to stabilise the economy and tackling the credit crunch, reducing the importance of private-owned banks (supporting a more democratic finance).

Financial markets and credit markets in particular are highly pro-cyclical: banks and financial operators lend too much in the upswing stage of the bubble and they escape when the bubble starts to crumble, producing credit crunch and a more painful recession. NDBs can stabilise the situation.

A bigger role for public banks not only allows for a reduction of banks’ myopia and markets short termism (as observed already by Minsky, 1996), it also allows for a more inclusive and democratic finance, because resources are mobilised for long term general aims and not for immediate speculative results that are counter-productive even for private finance after some months.

2.B Providing financial services in sectors or regions that private financial intermediaries do not serve sufficiently.

Financial operators are not interested in providing services at a loss. For instance, banks are closing branches in small towns because they are less profitable than the branches in the main cities. Although there is a transition towards digital-based financial services, many customers would like to have the possibility of choosing the traditional “physical” bank. Only because they live in a small town, they are excluded from this possibility. The same is true for specific niches of the market, specific products and so on. It is true that the cost of providing these services is different, say, in a mountain village of the Alpes than in a district of Rome or Berlin, but it is logical that the customers of the big town pay a tiny fee to allow banks to bring the services to everyone. This is true for every general service, like electric power, phone services, heating etc. It is obvious that if a family living in the Alpes should pay for the true cost of having the electricity lines to its doors, it could not afford it. Private operators can rationally select the sectors of the market that are interesting for them, even if it means excluding part of the population or they are heavily subsidised by the government. Only public operators can solve this issue: in fact, when in Italy, public utilities like energy (electricity and gas), water and phone networks were public entities (SOEs, municipal public companies etc.), they were managed as universal services. Without public intervention in these sectors, a large part of the population would be excluded from these basic services because these layers of the market are not profitable. Otherwise, they will be much more expensive to everyone.

3.B NDBs create a more diverse financial system.

When the global financial crisis hit the world, many commentators underlined that financial concentration, herd behaviour and other factors enormously reduced the diversity of banks and financial operators. As Haldane (2009a) observed: “In essence, the financial network has over time become progressively more complex and less diverse”. The marginalisation of cooperative banks and public banks played a decisive role in this process. After the crisis, more mergers and concentration ensued; therefore, diversity in the financial sector is even lesser than before 2008. There is no private solution to this issue because the only way to bring back more diversity is to reduce the role of private financial operators and their vagaries. NDBs can allow governments to partner with financial intermediaries on a fairer foot, thus developing a joint vision and expertise to fund projects in strategic sectors. A bigger role for NDBs could also help a general reduction of the weight of finance on the economy, which has been considered too big even by the IMF (Arcand et al., 2012).

We sum up the issues stemming from our analysis of rationale and aims behind NDBs.

NDBs are the only operators that can really plan long-term strategies, thus instilling more stability and less short termism into the financial system. Due to their long-term orientation, NDBs are also the only financial operators that can make a difference in the achievement of the SDGs and the green transition, whereas the private green finance only develops inasmuch as governments create a fiscal environment conducive to high profits. A 2017 EU report found an investment gap of € 1.77 trillion until 2030 (EU, 2017, p. 13). It likely widened afterwards. Due to these aspects, NDBs can make a difference also as far as innovation is concerned. More generally, NDBs are needed to fund sectors or activities where markets failures are widespread, for instance because social returns are higher than private returns; this is typically the case with environmental issues. This kind of investment is not attractive to financial operators although sorely needed. Mainstream economics reduces their role to cure markets imperfections; the point is that while policymakers are serious as far as the fulfilment of SDGs is concerned, private operators can only play a minor role because is the very structure of the problem that is intractable in a typical private investment analysis. The problem is not this or that imperfection, the point is reshaping the whole of the economy.

As for the specific situation of the EU, in an era of increasing European integration, public banks can be used as a way to compensate for the declining independence of national economic policymaking. Not only the monetary policy is the same for the whole of the area and national fiscal policies are forced into the Maastricht austerity framework, but also in the financial sector, after the creation of the Banking Union and the devolution of the banking supervision to the SSM-ECB, national policies became more and more irrelevant. Industrial policies are basically forbidden.

After exploring the possible deployment of NDBs for aims in terms of economic development and financial stability it is interesting to dive into possible objections to their role.

Table B – Possible critiques to National Development Banks

Possible objections and critiques to NDBs

Analysis and possible answers

It could serve to socialise banks’ losses or as a vehicle for offloading bad debts of State banks.

First of all, this happened also without NDBs (see the 2007-2008 crisis 6 ). We must distinguish between two kinds of banks’ losses. The first type is made of loans extended to ordinary firms that go bad because of individual mistakes of the firm or a general downturn. This is the ordinary job of the banks which should be compensated by the profits they make on their banking assets but which is passed to the State when the situation extremely worsens. NDBs should not be involved in these bailouts, which are better left to central banks and governments. The second type is made of the loans to specific projects that are very risky from the start because they are meant to change the technological landscape, the set-up of an industry and so on. It is obvious that in this activity, where the uncertainty is very high, losses are frequent, but they cannot be evaluated as an ordinary loan. This does not mean that NDBs should not be careful, yet there is no empirical basis to assess the credit risk of a changing technology or society. When banks and other operators fund a revolutionary technology, it is obvious that the rate of failure is high but the point lies in the importance of funding a revolutionary technology able to completely change its sector.

Misallocation of resources. For instance:

a) crowding out of private investment,

b) political interferences and unfair support to public firms

c) picking the winners.

A general answer is that, after the long series of financial crises of the 1990s and in the 2000s, arguing that private banks are better at allocating resources picking the right borrowers makes no sense. There are continuous examples of banks’ failure. As for the specific points.

a) Mainstream economics often objects that public investment crowds out private investment as if the resources of the society were fully utilized so that if the government invests, this forces private firms to invest less. Not only is this not the case, but funding coming from banks and financial markets can build new productive capacity thus also changing this limit. In reality, public investments are needed to ensure full employment and they should be used to this end.

b) Countless examples show that big banks and big corporations in general influence their governments. Financial regulation, fiscal policies and many other public policies are completely dictated by lobbying 7 . If NDBs succeeded in influencing public policies, this would be a welcome counterweight to private finance. In the last decades, big firms have been helped in many ways. Investigations such as the Panama papers show that big firms and banks have immense resources in fiscal paradises helped by the banks themselves (Bouvatier et al., 2017).

c) Provided that lending procedures and an efficient risk management are in place, an NDB has the same probability as an ordinary bank to pick the right project. For instance, the EIB (European Investment Bank) asset quality is very high, with non-performing loans at very low levels compared to ordinary private banks 8 .

Main characteristics of National Development Banks

We discussed why it is paramount to put the NDBs at the centre-stage of the financial system, and we replied to possible objections to this goal. Here we discuss single aspects of an NDB to better define its role.

We need bigger NDBs

To make a difference, NDBs should be a significant part of the credit system; this is especially true nowadays, given the importance of the large financial conglomerates. For instance, in the euro area, the first five private banks (BNP Paribas, Crédit Agricole, Banco Santander, BPCE, Société Générale) have total combined assets of around 8.2 trillion euros while the ECB has more than 8.5 trillion out a GDP of around 14.5 trillion. This means that, to have a meaningful role, the combined assets of the Eurozone NDBs should be of at least 2-3 trillion. The present situation lags far behind. According to Tucker (2022), the 27 European NDBs have “a combined balance sheet of 1.53 trillion euros, or about 4.6 percent of the total European banking system”. In the following graph we have a comparison of the European NDBs dimension vis à vis the national GDP.

(Nyikos, 2017)

A democratic governance structure of NDBs is possible

An NDB could choose a governance that mimics that of an ordinary bank, and it could even have private shareholders. The problem is that an NDB managed like an ordinary bank runs the risks of abandoning its development mandate, focusing too much on profitability, and competing with other private institutions. As for the EU rules, they are neutral as far as the ownership is concerned (art. 345 TFEU), although the general political idea of the EU on the issue is obvious: the less there is public interference along with profits by private firms, the better it is (Gaddi and Garbellini, 2017). The board of the NDB should be elected by the shareholders, i.e., public authorities and government, but it should have the possibility of technical independence, as it is the case with central banks. The narrative of public money wasted on useless projects is still very strong. It is important for NDBs’ behaviour to be as transparent and accountable as possible. In addition to the ordinary control mechanisms and bodies that we find in a bank or a public company (including the governance part of the ESG issues), the NDB functioning should include “governance from below”. An example could be, for every project, the setting up of an ad hoc commission with experts from central banks and public authorities, representatives of workers and of interested citizens. This commission should be in charge of verifying the effectiveness of the project and the implementation schedule. Individual commissions could be coordinated by a national structure that put together data, best practices, etc, to enforce a quality assurance mechanism. After being established for NDBs, this governance from below could be extended to the biggest state-owned companies (SOEs). Examples like co-determination in large German firms can give some hints of this “governance from below” but also of the limits they encountered so far (Page, 2011; Jäger, Noy, and Schoefer, 2022).

One of the most advanced experiences in the field of workers’ management were the Management Councils (Consigli di gestione) which were set up in 1945 by Italian workers in the factories to ensure the continuity of production in the companies after the disasters of the war and the attempts to destroy the plants by the occupying Nazi forces.

In the absence of general legislation, management councils were established, and functioned, in different ways in different companies, also depending on the balance of power between capitalists and workers. Their functions were also differentiated and could include: the reconstruction of companies, the resumption of productive activity, the increase and improvement of production, the employment of workers, functions relating to social and welfare problems (mutualism and company food outlets), the restructuring of plants, the procurement of raw materials necessary for production, the control of redundancies and transfers, etc.

The Minister of Industry at the time, the socialist Rodolfo Morandi, presented a bill to give an organic set-up to the Management Councils, also detailing their functions. In this project, the Management Councils were to become bodies of workers’ democracy, capable of exercising a wide range of functions, including being consulted by the company on the direction of the company’s activities and on its production and economic programmes; on the use and best utilisation of plants and materials; on the organisation of work and the employment of personnel.

In addition, they would have performed not only company functions, but also general functions: for example, their National Coordination would advise the Ministry of Industry on industrial policy issues, brief it about the production plans of individual companies, monitor the implementation of the industrial plans of individual companies and control data on production. Thus, the state would have had at its disposal a democratic instrument, from below, for the elaboration and control of economic policy, with roots directly in the places of production.

Unfortunately, with the break-up of the Christian Democrat-Socialist-Communist government, imposed by the USA, the new governments led by the Christian Democrats (1948) rejected any hypothesis of Management Councils.

Banking supervision

We touched on the supervision point, and we could ask, given that NDBs are banks (even if sui generis), if it makes sense that they get supervised by the ordinary banking regulators (in the Eurozone: the ECB-SSM structure). In practice, German KfW, French CDC, and the Italian CDP are not subject to the EU banking regulations, although there are often specific laws to control them (as the KfW Law, the supervision of the Corte dei Conti for CDP, etc.) which regulate them, and they are affected by some types of regulations such as European State Aid Policy. Now, banking regulation is a very complex and wide set of rules, and it is impossible to state that either all or none of them should apply to NDBs. To simplify, we divide them into three parts. The first one is composed of rules aiming to control the risks taken by banks in terms of leverage, liquidity, etc. These rules are not important for NDBs. Of course, they should operate with a capital and without too strong leverage but, given their public nature, the complex set of rules used to supervise ordinary banks could be swapped with a single rule about the leverage ratio (say, 3%) deemed as sufficient. The second one encompasses rules that deal with banks-customers relationship. Given that NDBs do not have ordinary customers, such as households, these rules are basically irrelevant for them. Finally, the third kind of rules is composed of those that regulate how banks grant loans (risk management tools, portfolio diversification, monitoring tools, reporting duties to credit bureaus, etc.). We think that, broadly speaking, NDBs should comply with this third set of rules.

Funding – the most important part

The main source of funding for ordinary banks is deposits (around 67% in the Euroarea); bonds are in a distant second place (14%), then equity (6%). Normally, NDBs do not have access to deposits, although with central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) it could change, because the central bank could share its deposits with the NDB 9 . At any rate, the funding source of NDBs is very differentiated (World Bank, 2017). NDBs that have good ratings can easily access international bond markets (see the ratings of some European NDB in the following graph).

(Nyikos, 2017)

As it often happens with SOEs, many NDBs receive direct funding from the government, others tap interbank markets (this is especially true of the KfW). The drawback of relying on the State is the political issue: a hostile government could reduce funding to subdue the NDB. However, also relying on the financial markets has drawbacks because of the vagaries induced by the instability of financial operators we described. For instance, since the beginning of 2023 we have seen a strong increase in interest rates, bonds included, hence in the cost of funding for operators relying on this source. After all, NDBs are interrelated either to the political trends of the country or to how domestic and international banking and financial systems work. At any rate, it is important, when discussing the funding issue, to underline that banks, including NDBs, do not have a fixed amount of funds they can rely on to make loans. In other terms, the old theory of loanable funds does not represent how the credit market works, as it has been explained even in mainstream works (McLeay et al. 2014; Jakab and Kumhof, 2015). This means that the asset growth target can be decided by NDBs on the basis of their internal strategies, not on some pre-defined quantity of savings.

The deglobalisation issue

After the 2007-2009 crisis, the globalisation of trade and markets has stopped. After the pandemic and the war, a deglobalisation trend will likely emerge. However, GSCs are and will remain fundamental in most sectors. The point is: how can a national NDB intervene in a global supply chain? Obviously, the role of NDBs is not to dispose of GSCs but to develop specific economic sectors and projects to boost growth and equality. The role of GSCs will remain, but they will change as we saw. More importance will be given to stability (both economic and political) and NDBs are ideal to overcome the paramount role of the immediate profitability, which is the only goal pursued by private firms. In the post-Ukraine war situation, it will be decisive to reduce the fragility of GSCs, something that ordinary banks and multinational firms cannot achieve. An NDB can address an industry as a whole, for example by assessing the overall industrial production capacity, or possible bottlenecks for critical parts and components.

Pricing and profitability

Banks, especially big banks, have made a lot of profits in recent years. Mainstream economics would conclude that higher profits mean that those firms are very well managed, but a bank is basically a producer of loans and in the case of financial instruments, loans or securities, a higher return is a signal of higher risks, not higher efficiency. In fact, making more profits also meant being potentially in need of public funds to be bailed out; overall, the behaviour of banks is based on the assumption that strong profits made in ordinary years are only partially reduced when a general crisis erupt, because losses are covered by the States thus allowing high profitability even during dramatic events like the pandemic (Fernandez-Bollo et al., 2021). As for NDBs, it is important that they follow economic principles, that is by equalising revenues and costs. Pricing in terms of market rates should be such that NDBs can make profits, but these profits should not be the guiding principle of their strategies. Whereas profits are the only relevant goal of an ordinary bank, for NDBs they are only a tool to fulfil their strategies.

Connection with fiscal policy

Broadly speaking, all governmental policy actions should be coordinated. In many aspects, NDBs are created to fulfil goals that are common to fiscal policy, such as full employment and economic growth. Unfortunately, the total dominance of the Maastricht Treaty framework in Europe has resulted in the end of full employment policies. While waiting for the end of that regressive framework, NDBs have an important role to play because, even in the present EU fiscal framework, they are free to pursue their goals. Indeed, an NDB whose behaviour would be determined by the EU fiscal straitjacket would not be able to achieve its aims, and this is besides precisely why we cannot consider the 2010 European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) nor the 2012 European Stability Mechanism (ESM) as useful in their present form.

It is true that, after 2008, the EU has acknowledged again the importance of State interventionism, even if only in the financial markets, and although the European Commission will attempt to strictly regulate when and how NDBs can intervene. After the pandemic and the war, it is advisable that these rules change. Despite these possible attempts to limit the intervention of NDBs, the key point is that they do not fall within the limits imposed on government borrowing. In fact, as stated by the European Commission (EC, 2015), their lending “is generally accounted for outside the general government statistics because lending decisions are taken at arm’s length from the government but the members of the NPB’s governing bodies are independent from the government. NPB operations meeting these requirements thus fall outside the scope of the EU Stability and Growth Pact, under these conditions”.

This governance condition (independence) is a political judgment, given that NDBs are owned by governments and the management of every company should reflect the aims of the owners. This is also reflected by the appointment of the Board of Directors which, where the government is the majority shareholder (as in Italy with Cassa Depositi e Prestiti), is appointed by the government (in Italy, the Board consists of nine members and is supplemented, for the management of resources from postal savings in the form of a Separate Account, by the Director General of the Treasury, the State Accountant General, and three representatives of regions, provinces and municipalities. A magistrate of the Court of Auditors attends the meetings).

Conclusions

From time to time, public policy proposals which once were far out

quite suddenly achieve social respectability – H. Minsky

Decades of anti-workers’ policies have left advanced countries with low growth, high wealth concentration, job precarisation, and under-funded public services. Propaganda on market efficiency and on the necessity of marginalising State functions, except when public money was used to save banks, has been superseded by the pandemic and the Ukraine war. However, the return of the State is now connected to the rearmament frenzy that is surrounding the entire planet. World military expenditure is already way above $ 2.2 trillion, and it is increasing fast. Green transition, eliminating poverty and hunger and many other SDGs have become secondary to the purpose of preparing for war. This is a dangerous path and one that labour and left-wing organisations should counter in the strongest terms. We need a bigger State role in the economy, but in order to proceed towards a fairer and more sustainable world. NDBs could be an important step in that direction. This paper is aimed at showing that another way of financing economic growth and the green transition is needed. Competition and herd behaviour make private investors and banks short-sighted. They are not interested in the long-term outcome of the economy and for the population. A stronger public intervention is needed, but with a qualification. In a situation of growing conflict among economic blocs, with the risk of a new cold war, a stronger role of the State in the economy is also likely but with aims, such as the rearmament of the West, deprived of any progressive intent. NDBs should be used to ensure full employment in Europe, not by building guns and tanks but by developing an advanced society where new technologies are used to eliminate pollution as well as poverty. Technically, most European countries already have institutions in place in a position to fulfil this role, the real issue is the political will.

References, Appendix, Footnotes

References

AA VV. 1922. Report of the Second Commission (Finance) at the International Economic Conference, April-May 1922

Antràs, P. 2020. De-Globalisation? Global Value Chains in the Post-COVID-19 Age, NBER Working Paper No. 28115, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Arcand, J., Berkes, E., Panizza, U. 2012. Too Much Finance?, IMF Working Paper No. 1527, International Monetary Fund, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12161.pdf.

Artola, I., Rademaekers, K., Williams, R., Yearwood, J. 2016. Boosting Building Renovation: What Potential and Value for Europe? Report for the European Parliament, PE 587.326; European Parliament, Brussels.

Auer, R. et al. 2021. Central bank digital currencies: motives, economic implications and the research frontier, BIS Working Paper No. 976, Bank for International Settlements.

Auray, S., Gouriéroux, C. 2013. Procyclicité des regulations des marchés financiers, LABEX no.4, April.

Bassanini, F., Pennisi, G., Reviglio, E. 2014. The Development/Promotional Banks: from the Financial and Economic Crisis to Sustainable and Inclusive Development, mimeo.

Bilal, S. 2021. The Rise of Public Development Banks in the European Financial Architecture for Development, ETTG-Elcano Royal Institute, Working Paper No. 12/2021.

Bouvatier, V., Capelle-Blancard, G. Delatte, A. 2017. Banks in Tax Havens: First Evidence based on Country-by-Country Reporting, EC Discussion Paper No. 55, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/dp_055_en.pdf.

Buiter, W. H., Rahbari, E. 2013. Why Do Governments Default, and why don’t they Default more often?, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 9492, Centre for Economic Policy Research, https://willembuiter.com/buchheit.pdf.

Caprio, J. R. 2020. Financial Regulation After the Crisis: How Did We Get Here, and How Do We Get Out? in M. Dewatripont, J. Rochet, J. Tirole, Balancing the Banks, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Carr, E. H., Davies, R. W. 1969. Foundations of a Planned Economy, 1926-1929, Vol I-2, MacMillan, London.

Clò, S., Frigerio, M., Vandone, D. 2020. Financial Support to Innovation: the Role of European Development Financial Institutions, Working Paper No. 10/2020, DISEI, Università degli Studi di Firenze.

Dieppe, A. (ed.). 2020. Global Productivity: Trends, Drivers and Policies, World Bank Group, Washington.

Dombret, A., Lucius, O. (eds). 2013. Stability of the Financial System. Illusion or Feasible Concept? Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

EC. 2015. Working together for jobs and growth: The role of National Promotional Banks (NPBs) in supporting the Investment Plan for Europe, COM(2015) 361 final, Brussels, 22 July.

ECSIP Consortium. (2016). The Competitive Position of the European Food and Drink Industry: Final Report, European Commission. Luxembourg, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/ 15496/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/pdf.

Erforth, B. 2020. The Future of European Development Banking. What Role and Place for the European Investment Bank?, Discussion Paper No. 11-2020, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik.

Fernandez-Bollo, E. et al. 2021. Euro Area Bank Profitability and Consolidation, Revista de Estabilidad Financiera, No. 40, Banco de Espana,

Flynn, B. et al. 2021. Introduction to Managing Supply Chains Beyond Covid-19 – Preparing for the Next Global Mega-Disruption, “Journal of Supply Chain Management”, 57(1): 3-6.

Gaddi, M., Garbellini, N. 2017. Public Tools of Intervention in the Economy: Meeting the Challenges of Trans-European Industrial Policy, Fondazione Claudio Sabattini and Associazione Culturale Punto Rosso.

Gaddi, M., Vinci, L. (eds.). 2019. Il dibattito sul controllo operaio. Rivista “Mondo Operaio”, Punto Rosso, Milano.

Giuffrida, A. 2023. Italy scraps green tax credit scheme as construction sector suffers, The Guardian, 27 February.

Goodhart, C. A. E. 2011. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision: A History of the Early Years, 1974-1997, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Gray, J. V., Skowronski, K., Esenduran, G., Rungusanatham, M. J. 2013. The Reshoring Phenomenon: What Supply Chain Academics Ought to know and Should Do, “Journal of Supply Chain Management”, 49(2): 27-33.

Griffith-Jones, S. 2016. National Development Banks and Sustainable Infrastructure; the Case of KfW, The Center for Finance, Law and Policy, The Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies, and The Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future, GEGI Working Paper No. 006 – 07/2016.

Griffith-Jones, S., Cozzi, G. 2016. The roles of development banks; how they can promote investment, in Europe and globally, Greenwich Papers in Political Economy No. 2016-11, University of Greenwich, Greenwich Political Economy Research Centre.

Griffith-Jones, S., Tyson, J. 2013. The European Investment Bank: Lessons for Developing Countries, WIDER Working Paper No. 2013/019, World Institute for Development Economics Research.

Haldane, A. G. 2009a. Rethinking the financial network, Financial Student Association, Amsterdam, 28 April 2009 https://www.bis.org/review/r090505e.pdf.

Haldane, A. G. 2009b. Banking on the State, Conference on “The International Financial Crisis: Have the Rules of Finance Changed?”, Chicago, 25 September 2009 https://www.bis.org/review/r091111e.pdf.

https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/GAP/ Secciones/Publicaciones/ InformesBoletinesRevistas/ RevistaEstabilidadFinanciera/21/4_Consolidation_REF.pdf.

High Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance. 2017. Interim Report. European Union, Brussels https://finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2017-07/170713-sustainable-finance-report_en.pdf

Jäger, S., Noy, S. Schoefer, B. 2022. Codetermination and Power in the Workplace, EPI.org, https://www.epi.org/unequalpower/publications/codetermination-and-power-in-the-workplace/.

Jakab, Z., Kumhof, M. 2015. Banks are not Intermediaries of Loanable Funds — and why this matters, Bank of England Working Paper no. 529, Bank of England, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/ Documents/workingpapers/2015/wp529.pdf.

Johnson, S., Kwak, J. 2010. 13 Bankers. The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown, Vinate Books, New York.

Katz, M. L., Shapiro, C. 1985. Network Externalities, Competition, and Compatibility, “The American Economic Review”, 75(3): 424-440.

Krenz, A., Strulik, H. 2021. Quantifying reshoring at the macro-level—Measurement and applications. “Growth and Change”, 52, 1200–1229.

Lampón, J. F., González-Benito, J. 2020. Backshoring and improved Key Manufacturing Resources in Firms’ Home Location, “International Journal of Production Research”, 58(20), 6268-6282.

Liebowitz, S. J., Margolis, S. E. 1995. Path Dependence, Lock-in, and History, “Journal of Law, Economics and Organization”, 11(1): 205-226.

Lombardi, L. 2023: Financial Crises as Wars, transform Europe, blog, 20 April 2023 https://www.transform-network.net/blog/article/financial-crises-as-wars/?tx_news_pi1%5Bfocus%5D=&cHash=f08a2f2bff3850acea381e6506d76c7e

Mastromatteo, G., Esposito, L. 2016. Minsky at Basel: A Global Cap to Build an Effective Postcrisis Banking Supervision Framework, Levy Economics Institute Working Paper No. 875, Levy Economics Institute, https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_875.pdf.

Mazzucato, M. 2013. The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths, Anthem Press, London.

Mazzucato, M. Penna, C. 2016. Beyond Market Failures. The Market creating and shaping Roles of State Investment Banks, “Journal of Economic Policy Reform”, 19(4): 305-326.

McLeay, M., Radia, A., Thomas, R. 2014. Money Creation in the Modern Economy, Bank of England Quarterly Bullettin No. 1, Bank of England, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/documents/quarterlybulletin/ 2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf.

Mertens, D., Rubio, E., Thiemann, M. 2020. Covid-19 and the Mobilitasion of Public Development Banks in the EU, EU Budget Policy Paper, European Union, No. 252.

Minsky, H. P. 1996. Uncertainty and the Institutional Structure of Capitalist Economies, Levy Economic Institute Working Paper No. 155, Levy Economic Institute http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp155.pdf.

Nyikos, G. 2017. National Development Banks for Better Public Spending, Paper for the 25th NISPAcee Annual Conference. VI. Working Group on Public Finance and Public Financial Management. Track 2: “Better” governmental spending as a reaction to the crisis.

Nyikos, G., Kondor, Z. 2022. National Development Banks in Europe – A Contribution to Sustainable Finance, “Central European Public Administration Review”, 20(1): 135-165.

Page, R. 2011. Co-determination in Germany – a Beginners’ Guide. 5. überarbeitete Auflage, Arbeitspapier, No. 33, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, Düsseldorf.

Palley, T.I. 2007. Financialization: What It Is and Why It Matters, Levy Economics Institute Working Paper No. 525, Levy Economics Institute, http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_525.pdf.

Reich, R. 2019. Socialism for the Rich, Capitalism for the Rest, Yes! Solutions Journalism, 26 April, https://www.yesmagazine.org/economy/2019/04/26/ socialism-for-rich-capitalism-american-economy.

Rosmino, C. 2021. Farm to Fork: EU Launches a ‘Code of Conduct’ for Healthier and More Sustainable Food Industry, EuroNews.green, 9 July, https://www.euronews.com/green/2021/07/06/farm-to-fork-eu-launches-a-code-of-conduct-for-healthier-and-more-sustainable-food-industr

Sandbu, M. 2022. The investment drought of the past two decades is catching up with us, “Financial Times”, 20 July.

Sanders, B. 2023. This country has socialism for the rich, rugged individualism for the poor, Twitter, 16 January, https://twitter.com/BernieSanders/status/1614983979362287616.

Tucker, T. N. 2022. The Rise of European Development Banking, “Finance and Society”, 8(1): 89-92.

Volberding, P. 2016. National Development Banks and the Rise of Market-Based Protectionism in Europe, Prepared for CEEISA-ISA 2016 Conference, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 23 June.

Whittle, M., Malan, J., Bianchini, D. 2016. New Financial Instruments and the Role of National Promotional Banks, European Parliament, DG for Internal Policies.

World Bank. 2018. 2017 Survey of National Development Banks, World Bank Group, Washington.

APPENDIX – Some examples of the use of National Development Banks

NDBs can be used in a number of industries and situations. We only give here some quick examples.

Transport

Mobility will have to radically change to meet the transition needs. The problem is not only to phase off oil as the main source of energy for cars, trucks, aircrafts, ships, but to totally reshape the industry. There is not alternative to a huge boost in public transportation to increase the efficiency of the sector and to reduce emissions. All the different modes of transport should be considered together to find the best solutions. Private firms are not able to do that, especially because each producer is not interested in the other modes of transportation. A public international program should be launched. NDBs would be the natural coordinators of such a project, as the effectiveness of a single investment is useless if it is not appraised in the overall context.

Housing

The housing sector is a key industry for the transition. The environmental impacts of buildings are huge, from the extraction and production of materials and components to the building’s use in its lifetime. In fact, buildings account for 40% of the EU’s final energy consumptions and 36% of its CO2 emissions (Artola et al., 2016). The importance of the issue also explains the strong EU normative efforts in this domain, in particular with the Energy Performance of Buildings Directives. However, the EU ideological approach is to fund private projects, for instance green mortgages, to favour the reduction in buildings emission. Of course, these projects are interesting, but absolutely not sufficient in regard to the speed and the scale required. What is needed is a strong increase in social housing. Cities must be reshaped with the goals of making them sustainable and socially inclusive. This does not fit into the private investment mindset, which rather aims to create costly islands of high-tech houses for the top of the market. Once again, only NDBs would have the competence and the prospective view to fulfil this goal. EU could set up a “housing bank” specifically aimed at this end, able to connect the industrial side of the issue (supply chains, the most efficient localisation of new projects, etc.) with the consumers’ side in terms of funding and social housing.

Food industry

The present situation of the food industry is simply unsustainable. It requires the continuous destruction of forests; it has a high impact in terms of emissions, and it is bad for farmers of emerging countries, to cite a few of its problems. It is connected to demographic issues as well as economic ones. For instance, the stagnation of workers’ income has affected the sector’s demand after the 2008 financial crisis (ECSIP 2016). In 2021, the European Commission, along with many firms of the sector, launched the “code of conduct”, a series of voluntary commitments to promote the shift towards healthier patterns for consumers and better production methods for the environment (Rosmino, 2021). It was an absolutely insufficient approach even before the war totally shattered all these projects. The sector needs a strategy that is not linked to the profits of the agribusiness giants but to the needs of the small producers and consumers. NDBs could be decisive in developing and funding long term projects to make the industry sustainable.

Footnotes

The IRI (Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale, Institute for Industrial Reconstruction) was an Italian public entity with industrial policy functions. Established in 1933, during Fascism, to save big firms destroyed by the depression, in the post-war period it gradually expanded its intervention, becoming the main tool of public intervention in the Italian economy. In 1980, IRI was a group of around 1,000 companies with more than 500,000 employees. As late as 1993, IRI was the seventh largest conglomerate in the world, with revenues of approximately $67 billion. When in the 1990s the Italian government launched waves of privatisation, it was transformed into a public limited company; after a decade it was closed.

For an analysis of the different European national situations, see Nyklos and Kondor, 2022.

The so-called “Superbonus” is the tax relief passed by the Italian government in 2020 which consists of a deduction of 110% of the expenses incurred by the implementation of specific interventions aimed at energy efficiency and static consolidation or the reduction of the seismic risk of buildings. The subsidised interventions also include the installation of photovoltaic systems and infrastructure for recharging electric vehicles in buildings. It was in place until 2022.

Reshoring is the practice of transferring a business operation that was moved overseas back to the country from which it was originally relocated.

A lock-in effect exists when firms or customers are basically forced to keep a specific technology because the change would be too expensive. A famous example is the QWERTY keyboard. A network effect happens when the value of a good or service depends on the number of its users. For instance, a social network is interesting for users and hence creates profits inasmuch as it is used by many other individuals, and so on.

It is difficult to assess the cost of the crisis because it affected public finances in many ways, but the numbers are enormous. For instance, with the crisis, central banks had to extend a sort of public insurance to financial operators’ assets. At the height of the crisis, the Fed granted $ 7.3 trillion of assets and the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation more than $2 trillion, the amount was over fourteen trillion taking into account all the public initiatives, such as the Troubled Asset Relief Program (2008-2013), the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (since 2008), etc. (Auray and Gouriéroux, 2013). Other measures reached “almost a quarter of global GDP” (Haldane, 2009b), around 150% of the US GDP (Johnson e Kwak, 2010), “between $60 trillion and $200 trillion” globally (Dombret, in Dombret and Lucius, eds, 2013), while, with the crisis of 1929, it was around 8% of US GDP (Il Sole 24 Ore, 22 March 2009).

For a clear example, the story of the Basel Committee and how its actions have always been influenced by big banks, see Caprio, 2010 and Goodhart, 2011.

https://www.eib.org/attachments/lucalli/ 20220270_eib_financial_report_2022_en.pdf.

Basically, every major central bank is discussing a strategy to create a digital currency. The discussion is both technical and political. The establishment of a digital currency of the central bank would radically change the financial landscape (for a recent discussion see Auer et al., 2021).